week 6 / 2026: plots and characters

Reading round-up: reports of literacy’s death may well be exaggerated; plot models are patterns, not blueprints; the “tapestry” novel, and the redistribution of character agency; extreme bird-watching, and the re-humanisation of the last hipster.

“All that’s left of me / is slight insanity / what’s on the right / I don’t know…”

Greetings from Malmö, where I am even more decisively bored with snow than I was last week. Welcome once again to WEEKNOTES at Worldbuilding Agency...

table of contents

among the pixels

I’ll start with this essay by Adam Mastroianni, in which he pushes back against the pervasive “death of reading” routine that’s been doing the rounds for a while. Mastroianni is not claiming that all is well in the house of text, but he’s arguing that it’s nowhere near as bad as it’s being made out to be—much like the much-prophesied arrival of a post-literate society.

Interestingly, he makes the latter point by reference to one of the touchstones of the decline-and-fall narrative, namely Walter Ong:

Most of the differences between oral and literate cultures are actually differences between non-recorded and recorded cultures. And even if our culture has become slightly less literate, it has become far more recorded.

As Ong points out, in an oral culture, the only way for information to pass from one generation to another is for someone to remember and repeat it. This is bit like trying to maintain a music collection with nothing but a first-generation iPod: you can’t store that much, so you have to make tradeoffs. Oral traditions are chock full of repetition, archetypal characters, and intuitive ideas, because that’s what it takes to make something memorable. Precise facts, on the other hand, are like 10-gigabyte files—they’re going to get compressed, corrupted, or deleted.

In truth I’m not sure I fully buy Mastroianni’s argument, here, though I think it does the decline-and-fall some serious damage. The riff toward the end, containing the Ong reference excerpted above, obliquely addresses what I’ve always assumed to be the biggest misreading of Marshall McLuhan, whereby one media is assumed to displace the ones that came before it. To the contrary, as the man himself observed, the content of a medium is always another medium: legacy media are ingested rather than being destroyed.

Put another way: if media are extensions of the human sensorium, then a new medium will treat the previous media as integrated prostheses, as components of that sensorium to be built upon; new media extend earlier media through incorporation. As a result, and the total media sphere becomes a reverse onion: every time you remove an outer layer, you reveal a larger and more complex system than was already apparent. Mastery of that system requires getting as close to the core as possible.

Which brings me to a variation on Mastroianni’s point, by a somewhat different route: text is not king, enthroned; rather it is infrastructure, interred.

Now I want to turn to some more practical story-stuff. Novelist Lincoln Michel is beginning a newsletter series on the importance of plot, and this first piece is on the dynamic of escalation—but I’m going to quote the introduction, in which he makes the case for plot per se, and describes his relation to the standard models of plot, such as the so-called hero’s journey or monomyth:

... there are commonalities between all those structures and guides. Most offer a variation on the following: a norm is established (exposition) that is broken by a change (inciting incident) which leads to a question (or conflict) that is answered (resolved) at the end (climax), leaving the character(s) themselves changed (resolution). The norm that is changed might be the character’s world itself changing (“a stranger comes to town”) or the character being forced to enter a new world (“a man goes on a journey”). The ending might be the character’s entire world changing, the character’s situation changing, or simply their mindset changing. These ideas are all well and good, although I find them somewhat limiting. A lot of interesting fiction doesn’t really fit this model unless you really stretch the definitions.

To say that one must learn the rules before breaking them is a cliché; more to the point, it’s not quite correct. What Michel is saying, I think—though perhaps because it echoes my own feelings on the matter—is that you have to recognise the most obvious patterns before you can develop your own combinations and variations. To that end, the standard models are useful as tools for analysis, or starting points; problems only arise when they are treated as templates or blueprints.

And, to be clear, problems really do arise, particularly when one model comes to dominate. The recursive influence of the Cambellian hero’s journey on Hollywood is much discussed, as is the leakage from the cinematic to the literary—but its dominance in the novel is comparatively recent.

The someone(s) in question are the novelists Ada Palmer and Jo Walton, who here discuss what they call protagonismos: “that quality some characters possess which means the plot will not advance until our hero comes to lead the action, be it to victory or defeat”. They also note that the nigh-total dominance of such focal characters in the novel is comparatively recent, since they came to replace what Palmer and Walton call the “tapestry” approach, which:

... had huge readerships. Many became blockbuster movies, reaching millions. And they’re all stories of multiple agency, often described on their back covers as “tapestries,” to tell us they have lots of threads, that we’ll be following lots of characters, whether it’s a few days in a luxury hotel, a week in Hong Kong, or millennia in an English village. In these decades—from the second world war to the late 1980s—tapestry books with multiple agency, many characters all shaping the outcome, was a major mode of bestselling books, and the blockbuster movies based on them. In these books there’s not a protagonist in sight, nobody the plot waits for, they’re all written in Dickensian multiple third: the point of view switches to whoever is most convenient.

What’s particularly interesting here is the connection that Palmer and Walton draw between the distribution of character agency and the choice of narrative mode—and I will be drawing on this argument for an essay of my own in the weeks to come. How do the narrative mode and the media used in the depiction and exploration of a world shape the sort of stories that you can tell therein? There’s no simple answer to that, and probably never will be—but believing that it’s a question worth asking is absolutely central to my work.

between the frames

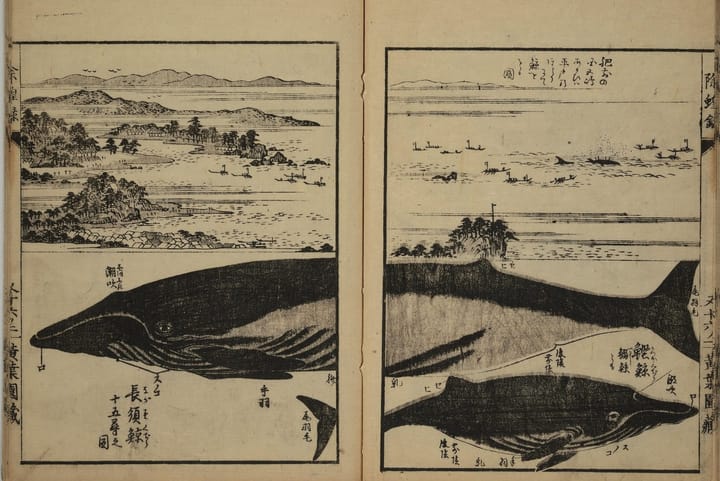

I finally finished Moby Dick this week—or is it that Moby Dick finished me?—and I’m giving myself a few days of recovery time before starting in on any more fiction.

In lieu of the usual discussion of a book, I’m going to make mention of the shoestring-budget bird-watching documentary Listers, which I watched on Saturday evening (thanks to a recommendation by the filmmaker Penny Lane, which I found via Austin Kleon’s weekly round-up of good stuff). It’s available in full and for free on Y*uTube.

Lane recommends not judging Listers by this promotional still, and I would second that recommendation. In truth, I went in expecting to last all of ten minutes before bailing out in eye-rolling exasperation, because Quentin (left), the focal character, really looks like the very last of the millennial hipster douche-canoes.

He kinda lives up to the look, to be honest, at least in some regards. But that may be why the arc of the film—which, to call back to Michel’s points above, makes deliberate and ironic use of standard model plotting—feels very effective: he and his brother (the filmmaker) set off to achieve what bird-watchers call a “big year”, initially in an ironic and undermining sort of modality, but eventually get caught up in the obsession (and the inevitable apps) that characterise the hobby. Seeing a character with such a studied jadedness as Quentin get genuinely caught up in something larger than himself is quite entertaining, precisely because it defies the expectations set up by our first encounter with him.

Indeed, one wonders how much Quentin’s character is true to life beyond the confines of the film, and how much is a creation of not only the edit, but also the very C21st instinct to perform a version of oneself that feels like it will be entertaining in the context. Lest this sound overly cynical, I consider us all to be caught up in that imperative to a lesser or greater extent: it is the consequence of growing up in a heavily mediated world.

What makes me curious is the extent to which we create works of art that train us not only to that instinctive performance, but to an awareness of it as performance. To someone of my age, the habituation of younger generations to the ubiquity of the camera seems ugly and alien—but to my parents’ generation, my own generation’s habituation to pop music and cable television was equally alien and threatening.

Quentin is a creature of his times; that he should seem somewhat alien to me is perhaps therefore only to be expected. But crucially, he seems nonetheless very human—and that, perhaps, is the point of stories: to recognise that essence across distances of time, space and culture.

lookback

This has been a slower, gentler work-week than the last one—a deliberate choice to dial back and give myself a break, and to focus on conversations with old colleagues and new friends alike. I feel better for it, too.

The timing is right, as well. Contra no less an authority than the Bard himself, I judge February to be the cruellest month, during which my ability to tolerate winter weather tends to vanish before the weather itself does, and where the perceptible change in the length of the day still serves mostly to show how slowly it’s changing. It is in my nature to be frustrated at this time of year; giving myself permission (and space!) to be frustrated seems a better option than trying to pretend I’m enjoying myself, y’know?

I’ve also learned that it helps to check the calendar: six weeks into the year, we’re only six weeks away from the spring equinox, and thus from what I think of as the “high side” of the year. You’d better believe I’ll be counting the days off like a kid counts the days to Christmas…

ticked off

- Seven hours of kinmaking and networking. (Calls, lots of calls! Would you like to have a chat? Well, then—go ahead and book one!)

- Seven hours of reading for research.

- Six hours of admyn.

- Five hours on PROJECT HORNIMAN. (A milestone draft is now with the client.)

- Three hours on these here weeknotes.

- Three hours of business development.

- Two hours of blogging.

- Two hours of focussed writing.

- And ten hours of undirected writing and reading, som vanligt.

OK, that’s everything for now. I hope all is well with you, wherever you may be.

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 06 of 2026. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe. If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend!

Comments ()