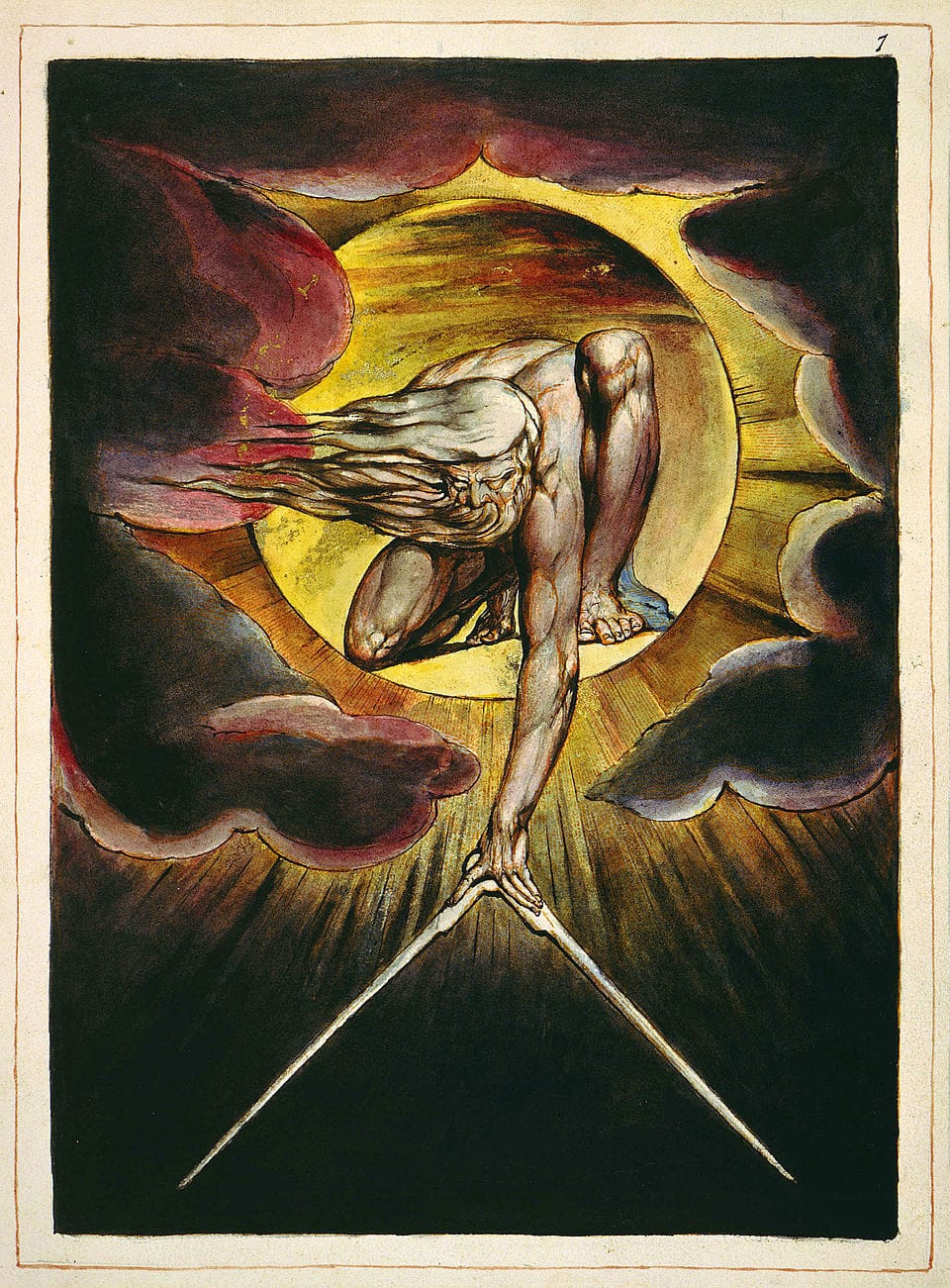

week 50 / 2025: ancient of days

Reading round-up: Auger disowns design-as-augury; a return to Turnton Docklands; a potted history of futurology; and an anarchist's analysis of utopian bureaucracy.

“I understand there’s no victimless crimes / that being said I feel rather victimized / and I will seek substantial compensation / whether legally, legal-ish, or otherwise...”

Welcome back to WEEKNOTES at Worldbuilding Agency. Without further ado...

among the pixels

This interview with OG speculative designer James Auger isn’t new—it was published in 2019—but it was new to me when it surfaced somewhere in this week’s trawlings. I want to clip this description of the underlying techniques of the form, which emerged in an early collaboration between Auger and fellow RCA student Jimmy Loizeau:

The techniques employed by [Orson] Welles bear many similarities to those used in the creation of convincing Speculative Design projects: the crafting of a complex narrative or artifice using the real-life ecology where the fictitious concept is to be applied, and taking advantage of the nuances of contemporary media, familiar settings and complex human desires or fears. The careful blurring of fact and fiction changes the way the audience perceives the concept and in turn their reaction to it.

A reminder that the designed object in such projects almost always needs some sort of framing, which in turn re-emphasises that, while they may not rely on (much) written prose, design fictions are nonetheless narrative interventions—built worlds.

I’m gonna double-clip this piece, actually, because the next paragraph also has some real gold in it:

... more important were the letters and email messages we received from all over the world, each voicing individual hopes and fears for such technology. This is the true product here – thoughtful and considered appraisals of what could go wrong with a product before it’s actually available, facilitating a more responsible approach to the technological future.

They really are prototypes, you know? You’re experimenting with ideas, but you’re trying to see what successes and failures might occur beyond the confines of the speculative object itself; you’re experimenting on the world that the object implies.

I’m reminded also of Bruce Sterling’s warning, way back when, that “design fiction has an audience, not victims”. But the form relies nonetheless on a certain degree of hoaxiness, a benign deceit, to achieve its best effects. One would hope that most people encounter a speculative design in the context of a tacit agreement similar to that made between a science fiction author and their readers: a tacitly negotiated suspension of disbelief. But one is also aware that the internet is a decontextualisation machine… and I can think of more than a few speculative projects that have had a long tail of enquiries from people who took them literally.

Indeed, one of the unavoidable limitations of material speculative work is that it doesn’t document well—an issue that is much on my mind, due to an ongoing writing project. Writing about design fiction or experiential futures is, to revive the old gag, rather like dancing about architecture: words are fundamentally inadequate to the task of capturing the experience and effect of these images, objects or environments.

A secondary downside is that it’s therefore very hard to “show” people a project that is no longer available for direct encounter. I will go to my grave regretting that I only heard about the 2017 Time’s Up installation Turnton Docklands years after it had first happened… and ever since I heard about it, I’ve wished there was at least a good write-up that I could point people at.

That latter wish, at least, has been granted: here’s Christl Baur of the Ars Electronica festival looking back on Turnton as one of her favourite exhibits:

In “Turnton Docklands,” visitors enter a harbor district in the year 2047. The starting point is grim: ecological tipping points have been exceeded, coastal cities are struggling with toxic waters, collapsing ecosystems, and extreme weather events. But instead of creating a pure dystopia, Time’s Up develops a fascinating counter-model. In the fictional coastal city of Turnton, a community has emerged that is finding new ways of living together in the face of crisis—solidary, self-organized, transparent, and supported by a sustainable economy.

There are some decent pics, too! Tim and Tina of Time’s Up are still doing great things, by the way—indeed, Turnton has recently rematerialised in Rostock, if you’re in the area—and I very much hope to get to work with them directly at some point. I really think this sort of experiential work is the future of futures: engaging, hopeful, and democratic.

Turning in the other temporal direction, here’s a link-rich overview of the history of futurology from the JSTOR blog. On the one hand, it performs the fairly standard reduction that has long since led me to avoid identifying as a “futurist”:

Futurology, as it is sometimes known, is the practice of making predictions about the future according to one’s claim to it. A futurist, then, not only imagines what the future might look or be like, as a philosopher or science-fiction writer may, but imbues their predictions with a paternalistic authority over the future that they envision, an assurance of its inevitability, and, in some cases, access to the means and the resources to make it happen.

Ugh. The history being traced here is of what friend-of-the-show Andrew Curry calls the “intuitive logics” school of futures work—a line that runs from RAND through GBN and on to today’s Big Consult operators, but which in Pitre’s telling extends much further back, taking in such diverse antecedents as the Italian Futurist art movement and, uh, Karl Marx?

While I’m glad to see that line being traced more frequently by folk outside the field—and have clipped this as a worthwhile read for that reason—it’s a shame that the more creative, exploratory and story-driven “shadow” discipline, which has existed in parallel since at least the end of the second world war, tends to be airbrushed out of such accounts. Andrew’s opening essay for the Handbook of Social Futures is a good corrective to that, albeit one regrettably trapped behind the academic paywall. The late John Urry’s final book, What is the Future?, is also a very readable expansion of the story.

between the pages

This week I’ve been rattling my way through an early work by the late David Graeber.

Less a book than a bundle of three long-form essays on related topics, The Utopia of Rules starts from a typically Graeberean premise: few fields of human endeavour are more universally despised than “bureaucracy”, or so you’d think from the way we talk about it. But Graeber here delights in showing us that not only is governmental bureaucracy inherited wholesale from the corporate sector that tends most loudly to decry it, but bureaucracy more broadly also has an oddly utopian set of aspirations associated with it, despite that whipping-boy status.

I’m not going to go into to much detail on the arguments, as I plan to write about this book at greater length in the coming weeks. Suffice to say that it’s a early example of Graeber completely upending a deeply entrenched assumption about how our world works, and then shaking it until the contradictions are cascading from its pockets.

It’s also a reminder of what we lost when he died a few years back. Graeber wrote with great wit as well as clarity, and was adept at making complex political and social ideas accessible to a wide audience, all while declining to pull any critical punches whatsoever. I admired him from a political-philosophical point of view, because he was that regrettably rare example of a publicly “out” anarchist intellectual who didn’t make me want to dis-identify with that position—but I admired him still more as a writer. I have his typically simple aphorism, “Be kind to your reader!”, taped to the wall above my monitor—an instruction which, admittedly, I honour most often in the breach.

lookback

This week was something of a lull week, and not entirely by choice: put plainly, I had bigger plans, but I lacked the energy and focus to match them. So this week’s tally features a lot of admyn hours that were distinctly futz-y in character, and bits of reading and writing that were arguably more recreational than professional.

I am, however, doing my level best not to berate myself for this. The last few months have been very intense, after all—and exploratory reading and writing (and thinking!) is an important part of a creative practice. But one is confronted, in these circumstances, by the extent to which one has internalised the dogma of productivity: restorative time is all too easily interpreted as squandered time, and the boss-in-the-head does not appreciate the squandering of resources that might be more efficiently exploited.

Luckily for me, the boss-in-the-head is my only actual boss, which means the consequences of flipping him the bird are fairly minor.

ticked off

- Eleven hours of networking. (Some in-person, some online. Some new faces, some familiar ones.)

- Ten hours of admyn. (I know I did the hours. I’m not so sure what I did with them, if you see what I mean? And here we find the essence of the argument against Urizen and all his works: just because you’ve counted something, doesn’t mean you’re in control.)

- Five hours of writing. (Including more notes toward a piece of fiction, and a spontaneous and rather sprawling blog post over at VCTB. I’m very out of practice at blogging as a form—not that I was ever exemplary with regard to the brevity thing, mind you.)

- Four hours of research reading.

- Three hours on these here weeknotes.

- One hour of logistical run-around. (Retrieving various bits and bobs which were still on-site at STPLN.)

- Ten hours of undirected writing and reading, as always.

Well, there we go. I’m going to spend the rest of Sunday doing art stuff, because I haven’t done any in ages, and I think the shape and texture of this week is a strong indicator that some creative (and, crucially, non-verbal) play is required! I hope all is well with you, wherever you may be.

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 50 of 2025. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe. If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend who you think might also like it!

Comments ()