week 48 / 2025: walking in the shadows

Reading round-up: dead media theory revisited; the quantified self, Victorian style; two takes on a rising China; and Aleister Crowley’s proto-pomo mental hygiene routines.

“Offer me the bait and I’d take it / offer me the cake and I’d bake it / usually I’d try to fake it / but these days I’d rather face it...”

As promised, weeknotes have a new format! I’m going to begin with a selection of clippings from this week’s online reading—I’m thinking three to five is a good batch size to start with—followed by a look at one of the books in my current stack. Then I’ll move to a little reflection on the work week, and the obligatory tallying of time. Those of you uninterested in the latter half should feel free to skip out after the top half!

As a reminder, essays will be returning in the new year, but less frequently, in order that they might be of better quality. They will also come out separately from regular weeknotes! If you’re getting WA by email, please note that you can log in and adjust your preferences regarding which material you get sent—which is to say, if you’re only here for the essay-type stuff, you can opt out of weeknotes and declutter your inbox a bit.

(You can always unsubscribe completely, too. I’d be sad to see you go, but I get it: it’s a noisy, noisy world, and I’d rather be signal or silence.)

among the pixels

Bruce Sterling has dug up and republished an old talk from the closing days of his Dead Media Project. (Said talk had been lost to linkrot, which is pretty much a textbook case of irony.)

This was a conclusive speech of mine at the end of the “Dead Media Project.” That project ended with my realization that its premise was wrong. Media do not live and die for mediated reasons. Media die because they are built on simpler technical substrates, and those substrates collapse.

In summary: the “magic lantern” dies because the lantern dies, not because the magic dies.

Lots of good stuff in there, as always, but I think the big take-away is the ease with which we forget the lessons of even the fairly recent past, particularly with regard to sociotechnical change. The concerns being aired in this piece, of twenty years vintage, are just as pressing in the present, if not perhaps much more so.

(For more of the Chairman’s wisdom, see parts one and two of my interview with him from awhile back.)

From dead media to a sort of revenant form... or from dairy to diary, if you prefer the puns. This Aeon essay makes the case that much of our oh-so-modern obsessions with quantification and self-improvement can be laid at the feet of the Victorians, and in particular their obsession with diary practices.

... the great Victorian innovation in diary-keeping was the switch from the use of the diary solely as a means of reflecting on past actions to the use of pre-printed diaries to plan the future. Diaries were no longer just a record of experience; they were an organisational tool. A mania for progress, industry and commerce had seized the nation, trade was flourishing in the bustling capital, and these new times generated new commodities. Tasks, appointments, memoranda – all could be jotted down in a neatly structured pocket diary that would help you use your time as productively as possible.

I’m a little leery of arguments that seem to blame current ills on earlier eras. But read alongside Bruce’s bit above, this one can maybe take us more in the direction of considering certain attitudes to the private and social self as being continuous through time, but rising and falling like the tides, and manifesting in new ways through the productisation of new media.

China has been much on my mind, as it featured strongly in a recently-finished project—but of course it’s on everyone’s mind, for a variety of reasons. A couple of pieces from this week’s Ideas Letter bring some useful perspective.

The first sees the redoubtable Owen Hatherley turning trash to treasure by writing about what he learned from binge-watching the recent surge of China-tourism vloggers:

On an average day, several of these videos are promoted into my feed, and they all look the same. Usually the little thumbnail that I can click on to watch the video will feature two young, thin people against a futuristic architectural backdrop, with the name of a city—Shenzhen, Shanghai, Chengdu, and Chongqing are the most frequent locations—with the words “CHINA SHOCKED ME!” They can’t all be shocked, you might ask, particularly given that they all visit the same places.

Then we have Afra Wang responding to a piece from the same venue a few weeks back, and helping us see China—both the actual country, and the confected fiction of its popular representation in the West—through eyes that are both an insider’s and an outsider’s.

I grew up in a time when the United States still radiated a kind of unquestioned allure. Apple’s iPhone 4 was an object of worship in my high school. China was rising, but not yet glamorous. If you told my teenage classmates that American kids in 2025 would look to China for inspiration, they would have laughed. But something has changed. The drift is subtle but undeniable.

Last but by no means least, a long deep cut for the word-nerds: Sam Kriss takes as his point of departure last week’s recrudescence of the periodical ding-dong between analytical philosophers and the straw dummy they call “continental philosophy”, and turns it into a typically entertaining enquiry into writing, style, and philosophy in general.

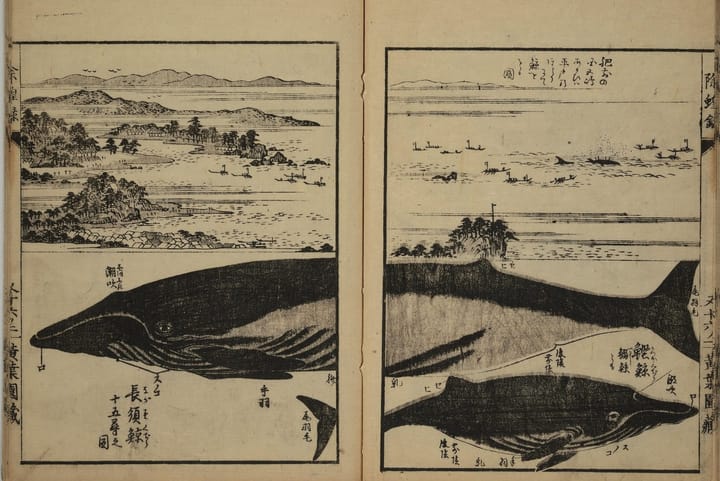

I’ve reread this passage several times, and every time it generates a sudden mental image of whales, huge humpback whales on a black moonless night, glittered with barnacles, wheeling their great ungainly heads just beneath the frothy surface of a white-webbed sea.

According to a lot of people, this is not important. Summoning beautiful mental images of whales is not one of the proper functions of philosophical language. I want to argue that a lot of people are wrong.

between the pages

This has been a busy week socially, which has meant my offline reading time has been somewhat fragmented. In such circumstances, what you need is a dippable book—something that won’t suffer from your only being able to go at it in short bursts.

As a result, I’ve been reading Magick Without Tears by the Great Beast himself, Aleister Crowley. This book takes the form of a collection of letters from Crowley to an aspiring practitioner of the magickal arts, which is just perfect for dipping.

I’ve been studying the occult on and off since my early teens, but back then it could be hard (or expensive, or both) to get your hands on the really legendary works. I read some Crowley over the shoulder of a fellow psychonaut while still at school, but never really got to sit with the guy’s stuff properly—which is probably for the best, as I would not have appreciated or even understood much of it.

MWT is perhaps the most accessible Crowley, thanks to the epistolary format, but it’s also an insight into the man behind the (often ridiculous, partly self-constructed) legend. He was clearly an incredibly intelligent, driven and well-read man, rather than the woo-woo fruitcake you might expect.

(Yes, he made some highly questionable decisions, and often treated people in his orbit terribly, and I make no excuses for any of that. But we have as much to learn from devils as from saints—not least the slippery subjectivity of such labels.)

The Crowley we meet here is not a person who has turned their back on the cutting edge learning of their era: he’s well versed in chemistry, mathematics, anthropology and philosophy, and cites contemporary thinkers in a way that suggests comprehension and synthesis. Furthermore, he sees no essential contradiction between all that modern knowledge and the ancient wisdoms that underpin the occult stuff. Quite to the contrary: for example, he keeps insisting on careful record-keeping around one’s magickal experiments and the application of statistical methods to the results. This is key to not mistaking one’s own imaginings and wishful thinking for the actual manifestation of whichever powers or entities one has been trying to evoke—an attitude one fervently wishes was more prevalent in the world of foresight in what we keep being told is the “age of AI”. There are a whole lot of folk out there right now who believe they’ve been talking to angels, or that they’re building a new god to worship; that rarely ends well, as the mishaps of occult dabblers strongly suggest.

Perhaps most interesting, however, is the potential for seeing Crowley as a proto-postmodern thinker, way ahead of his time. That he’s citing Nietzsche is not entirely surprising, but I was a little shocked to see him refer to Saussure, harping hard on semantics and a close, deconstructive attention to words and language as crucial not only to magickal practice but also to staying afloat in a world saturated in deceptive narratives and ideologically biased media systems: as with the statistics and the scientific method, the objective here is to avoid (self-)delusion and deceit.

This, I realise, is why I’ve been drawn back to occult studies in recent years: far from being the mystic mumbo-jumbo it’s assumed to be, the core of magickal thinking is an insistence on seeing through illusions, and disciplining one’s own imagination in order to construct narratives that will help you survive the discursive battlefield.

There is, sad to say, a strong historical rhyme between Crowley’s hey-day and our own turbulent times: old certainties exhausted, vacuums of power and opportunity, yawning chasms of comprehension. Crowley witnessed two world wars—indeed, he claimed to have prophesied both of them, which is perhaps best understood as less a magickal act (despite its being couched in magickal language) and more a matter of being attentive to the zeitgeist and resistant to other people’s hype and bullshit.

One sincerely hopes we won’t end up in such drastic forms of conflict in our own age—but one would be a fool to assume it impossible.

lookback

This week has felt like a sort of pre-emptive end of the year, for an assortment of reasons. A couple of projects have come to an end; we had the “moving on” session for my cohort at STPLN; and Media Evolution’s Vinterfesten, which has come to serve as a sort of nearly-home milestone for my business year, ran a little earlier than usual, this Friday just gone.

Plus it seems I’ve managed to match last year’s turnover in eleven months—which is not exactly the most spectacular example of business growth, but nonetheless feels like a good result in the circumstances. There’s still stuff to be done before the new year rolls round, but I should also have a bit of space for thinking out what I want to do with 2026.

I did a batch of tarot readings at Vinterfesten, which I felt went really well, though doing three sessions end to end was a salutary reminder that they’re pretty hard work: you have to listen closely—and empathetically!—to a person you’ve literally just met, while also exercising the same sort of pattern-recognition and interpretation routines that you might run in the scenario-building stage of a foresight project, albeit at a somewhat different scale.

But what a privilege, to be trusted with people’s hopes and fears, and to help them take a fresh look at their situation! I really enjoyed it, and have taken the experience as an endorsement of my plan to deploy the cards as a kind of tactical foresight tool that’s accessible for people with smaller businesses and projects.

(I still haven’t worked out a satisfactory way of doing this work online, which would be a much more “scalable” business proposition. But I think it would also dial down the very thing that makes the process work, which is the special sense of a private discussion mediated only by the cards? Anyway, something for that list of things-to-consider in December.)

ticked off

- Nine hours of kinmaking. (Most of this was a full day at the EIT Culture & Creativity project’s Resilience Dialogues at MEC. Interesting things afoot here, it seems, though perhaps somewhat hobbled from the outset by the tortured and impenetrable language of the funding apparatus. It’s very hard to find one’s way in to this sort of scene as a one-man band, so I’m aiming to forge some useful alliances and get shown the ropes.)

- Nine hours of admyn. (Bits, bobs.)

- Five hours on PROJECT FLATPACK. (This one’s all over bar the shouting, I think.)

- Five hours on these here WEEKNOTES.

- Three hours of tarot consultations.

- Three hours of off-boarding at STPLN.

- And twelve hours of undirected writing and reading, as I managed to squeeze some extra scribbling into gaps between other activities.

(Also six hours under the needle with my tattooist, which accounts for a slightly low total tally.)

Right, that’s all for this week. I hope all is well with you, wherever you may be.

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 48 of 2025. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe. If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend who you think might also appreciate them!

Comments ()