week 46 / 2025: eyes on the street

So, you’re writing a short story that’s meant to explore a future. What’s the first and most crucial step in the process of getting your imagined world onto the page? It’s not what you might think...

“A creature’s waiting for a battle in the ancient swamp / your pissing on the pyramids ain’t gonna move things along...”

I find myself far more preoccupied with matters of story in the cold, dark winter months—perhaps because this is the season in which our forebears would have spent more time sat around sources of heat and light, telling tales to make sense of their world.

Those forebears had the advantage of a shared mythology that explained how things came to be the way they were. When you’re trying to tell stories about imagined futures, however, you’re in the position of having to explain not only how the world works, but how it got that way. These are the Janus faces of worldbuilding: yes, you have to imagine that world, but you also have to use the tools of fiction to transport your reader there.

The temptation is to get all the details down in front of the reader as soon as possible. You’re excited about the world, there’s lots of things about it you want to get across, but you’ve only got a few thousand words—maybe less—to work with. For the same reasons, you want to give the reader an immediate sense of displacement and futurity, and get them to what I sometimes call “the Toto moment”, i.e. the moment when they get a feeling they’re not in Kansas any more.

This instinct is understandable, and widespread among beginning writers. Unfortunately, it’s almost completely wrong. The first thing to do is to establish your point-of-view character.

Your story needs a character upfront because you need to introduce your reader to your imagined world gently. If you just bombard them with neologisms or descriptions of how different things are, they’re going to feel baffled and adrift.

Now, you might think that’s the point of the exercise. Don’t we want to help our audience explore the changes we’ve been imagining? And yes indeed, we do—but, somewhat paradoxically, the best way to illustrate radical change is to present it as if it were totally normal and everyday, and as it would be experienced at ground level.

Establishing your character in the first few lines gives your reader a pair of eyes through which to see—and, crucially, a suite of other senses. Sight is our dominant sense, but we also hear, smell, taste and touch. (We also feel emotions—though you wouldn’t know it, to judge by a lot of foresight work!) Certainly we have rational responses to our experiences, but rationality is ex post facto: first, we sense, and we feel. And so, if you want to take your reader into your imagined future, you need to make them sense and feel it by proxy.

I have mentioned before the writerly aphorism “show, don’t tell”. This is best thought of as a rule of thumb rather than an iron commandment, but for writers beginning their journey—or simply writers beginning a draft!—it’s wise to keep it front of mind. It’s not impossible to evoke an emotional response from straight description in prose, but it’s much easier (and more powerful) to evoke an emotional response through empathy.

When we read of a character sensing things, feeling things, we sense and feel along with them. Instead of simply looking at a picture drawn with words, we find ourselves imagining ourselves into the scene, as if we were sensing it through the character’s body. This is not only much more vivid, but much more efficient: once the reader’s imagination is engaged, it will fill in all the detail that you don’t have the wordcount to include. You don’t need to describe everything, only what’s really important to the story.

Of course, you still have to decide what to describe, and how—but again, this is where having a character in play is really helpful, because it forces you to think about what they would and wouldn’t notice or remark upon. To reiterate: if you’re trying to present a world in which radical change has taken place, you need to remember that for the inhabitants of that world, that complete change will have become their baseline normality.

A comparison with history might be helpful, here. While to us they seem novel and alien, the inhabitants of Victorian-era London likely didn’t spend much time remarking upon the ubiquity of stove-pipe hats and horse-drawn carriages, any more than the inhabitants of today’s London spend much time remarking upon the ubiquity of baseball caps and the underground network.

Now, that’s not to say those Victorians would never discuss such things at all. To the contrary, our hypothetical Victorian Londoner would certainly notice a stove-pipe hat, because it would tell them something about the class and status of its wearer; furthermore, public discourse around the end of the C19th was quite preoccupied with the ubiquity of horses, because they produced a staggering amount of horse-shit.

But if you were being shown around Victorian London by our hypothetical inhabitant, they wouldn’t begin by pointing out that the majority of public transport was horse powered, because they would assume you’d already know; it’s normal, it’s just the way things are.

So perhaps we could coin a foresight-specific remix of “show, don’t tell”, which might go something like “consequences, not change”. Don’t tell me that your future world has flying cars; instead, show me the queue at the taxi-rank halfway up the hundred story residential tower; show me the signage explaining the parking fees at street level as they apply to different sorts of vehicle.

(Not at all incidentally, this is why design fiction is such a powerful technique: it doesn’t tell you about a future from the top down, it shows you a future from the bottom up. However, as they have their roots in cinema, the narratological rules of diegetic prototyping work rather differently to written fiction, so it’s best not to try stealing tricks from visual and material storytelling until you’ve got a good grasp of the native affordances of prose.)

The trick of fiction for foresight is the portrayal of futures not as futures, but rather as the everyday present of the people who will inhabit them. By making your imagined future normal for its inhabitants, you bring its strangeness to life for your reader in the present. The early establishment of a viewpoint character is absolutely key to achieving these ends.

If you found this interesting, and would like to learn more about how to turn futures into fictions, then I have just the training course for you! Tuesday 20th January to Thursday 22nd January 2026, Malmö, Sweden: an intensive three-day foundation course dedicated to writing fiction specifically for futures and foresight outputs. Click through for more details and registration:

reading

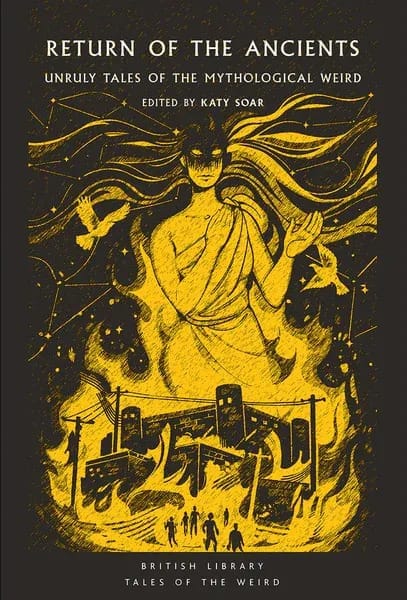

This week I’ve been reading a bunch of short stories from an anthology in the British Library’s Tales of the Weird collection. Each anthology is loosely themed, and the one I’ve been reading is called Return of the Ancients, featuring stories whose protagonists have encounters with manifestations of ancient deities and mythological figures.

The editors get to draw upon nearly two centuries of short fiction from the BL’s collections, which means that the quality can be somewhat variable, especially with the earlier pieces—but that means you get to see the evolution of the techniques that come to define the genre. I suspect it has also contributed to my having questions of character and worldbuilding on my mind: much as in science fiction, which faces similar technical challenges, the early works in particular tend to feature cardboard cut-out characters and clunky exposition.

But weird fiction in particular tends toward clever uses of form and frame. This is partly historical: stories from the era of widespread written correspondence naturally lean hard on the conceit of letters left to posterity, for example. I have a particular fondness for the framing device sometimes known as the “club story”, very common in classic weird fiction, in which the tale itself is delivered second-hand, recounted by the narrator as they supposedly heard it from some friend, colleague or acquaintance; a famous example would be Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

I find it a fun form to write—indeed, my first published piece was a club story, though that was less by choice than due to the underlying conceit of the book in which it appeared—and reading a bunch of them has caused me to realise that it’s a big influence on my narrative prototyping work. Embedding a tall tale in a familiar medium does similar work to the establishment of character, in that it gives your reader something comfortable to cling to when the going gets strange…

a clipping

Yup, it’s another Aeon joint. In this somewhat technical piece, the author discusses the inherent and inescapable shortcomings of the software-based Earth System Models on which we base our speculations about climate change and how it will manifest locally.

The increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are driving the climate system into a never-before-seen state. That means the past cannot be a good guide to the future, and predictions based simply on historic observations can’t be reliable: the information isn’t in the observational data, so no amount of processing can extract it. Climate prediction is therefore about our understanding of the physical processes of climate, not about data-processing. And since there are so many physical processes involved – everything from the movement of heat and moisture around the atmosphere to the interaction of oceans with ice-sheets – this naturally leads to the use of computer models.

But there’s a problem: models aren’t equivalent to reality.

What’s particularly interesting for me is Stainforth’s description of two schools of thought around these models, one of which argues that the models must be made ever more powerful and granular in order to become better at predicting local outcomes, and one which (as I understand it) argues that we’d be better off using the models as the basis for a more qualitative, situated approach that relies on what Stainforth labels “storylines” for exploring possible outcomes in particular places.

Those “storylines” are not quite the literal narratives that I recommend in my own approach to thinking about futures on the basis of limited empirical data, but they’re analogically close enough that it’s very gratifying to see. The sciences have seemed for some time now to be coming round to to the limitations of simulation that Jorge Luis Borges managed masterfully to capture in half a page, in a time before computers (as we conceive of them) barely existed… if only the engineers were a little closer behind the rest of us!

ticked off

- Fourteen hours of admyn. (Lots of catch-up, here, plus correspondence—though I’m still very behind on the latter, so if you’re waiting on email from me, I thank you for your patience!)

- Twelve hours on PROJECT FLATPACK. (Meetings, planning, editing.)

- Five hours on PROJECT MORPHOSIS. (Writing, particularly character development.)

- Three hours of research. (Kicking ideas around for something I’m hoping might come off in the new year.)

- Three hours on these here weeknotes.

- Ten hours of undirected writing and reading, som vanligt.

A somewhat slower week, then—though I’ve worked a lot over the weekend to compensate for some social time taken during what would usually be office hours, and to bolster against the fair amount of running around that’s to be done in the week to come.

Right, that’s all for now—there’s a bit more work to be done today before I can down tools and do my domestic stuff. In the meantime, I hope all is well with you, wherever you may be.

Comments ()