week 45 / 2025: ten theses on “the future”

The moment to change a mental model is the moment at which it becomes an obstacle to understanding rather than a scaffold for it.

“This is a film about the future / it is the future of your life / you think it’s certain / but nothing is certain…”

Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends! This weekend has been all about decompressing from a solid twelve-day run of work, and—in this household, at least—decompression and philosophy go hand in hand.

(Or, for the sake of making the metaphor more accurate, decompression and philosophy sprawl on the sofa next to one another, drinking an Eriksberg Pale and playing Tactical Breach Wizards.)

I thought I’d try something a bit different in terms of form for this week’s essay, and I’d be interested to know what you make of it! So please scroll on for ten short theses on “the future”…

- The moment to change a mental model is the moment at which it becomes an obstacle to understanding rather than a scaffold for it.

- The relatively recent emergence (and strange architecture) of future tenses, in those languages that even have such a thing, rather implies that human beings got along without “the future” for the vast majority of our existence. Getting an idea into a language is much easier than removing one; changing the way an idea is thought—and the ways it is thought with—is also hard, but presumably less so.

- Jonathan White’s In the Long Run argues that the rhetoric of urgency is politically damaging, and a driver of the very short-termism that it proposes to correct. Orienting toward “the future” as a location in time—again, definitive and singular, even if also implicitly plastic and partially open—does something strange to our attention.

- Once you’ve tacitly agreed to a linguistic map of time in which there is one definitive and inevitable future, you’ve also tacitly agreed to a political struggle over what it will look like—over which future, or rather whose future, we’ll all end up inhabiting.

- The problem with “the future” is that it has become fetishised, a sort of rhetorical obsession—like a meme, if you like, just bigger and slower than the pop-cultural blips that we tend to associate with that term. Indeed, “the future” is very much a meme in the original Dawkinsean sense of that term: an idea which has successfully colonised human beings as a means to its own reproduction. But what was once a symbiosis has become something much closer to a parasitism.

- Put another way, we could say that “the future” is discursively over-privileged. It’s not that thinking and talking about “the future” is bad, so much as that we spend too little time, relatively speaking, thinking about the past. But of course “the past” actually bears a lot of the same conceptual shortcomings as “the future”: definitive, singular, monolithic, etc. (It’s not that conservatism doesn’t have utopias; it’s that conservatism’s utopias are always located behind us in time, rather than ahead.)

- The definitive future began to solidify and dominate during the period in which scientific modernity was gleefully dismantling the old assumptions about what had gone before: as “the past” became less a source of comfort and continuity, perhaps we sought those things in its opposite?

- We would do well to pay much greater attention to history—not as a replacement for the attention we currently pay to futurity, but rather as its counterbalance. Our problem is not in the duality between these two orientations, but rather in the rigidly either/or approach we take to them: the assumption that we can only be looking one way or the other. We can of course look both ways, as our parents wisely taught us to do when crossing the road.

- When we over-privilege the future or the past, what we lose is the present—and the present is the only temporal location in which action can be taken. The future and the past both encase us in the amber of causality: either we’re trapped in the solidified decisions and structures that were laid down before us, or we’re treading a tightrope toward some over-hyped yet under-examined sociotechnical omega point. Both these attitudes are narrowly determinist: call them fate and destiny, respectively.

- But in the eternal words of Sarah Connor: “there is no fate but that we make”. For all their ostensibly being about “the future”, the Terminator movies—or at least the first two; I’ve not kept up with the bloating expansion of that franchise—are trying to tell us the only way we can shape tomorrow is by doing good things today.

reading

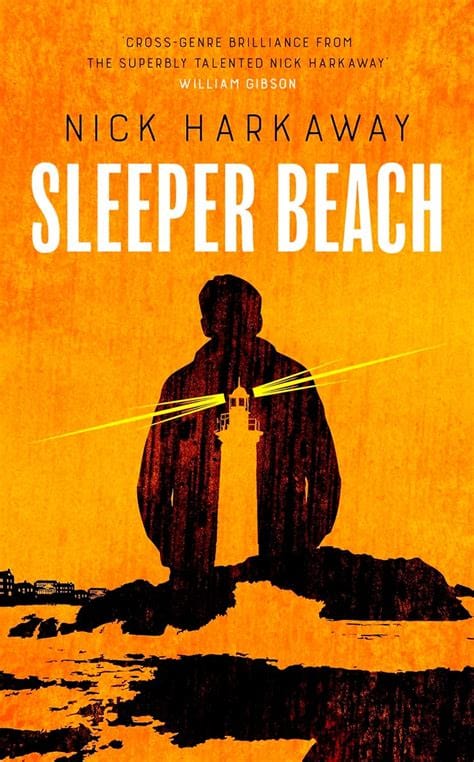

From the father to the son: having finished The Constant Gardener, I turned to the latest novel from le Carre’s literary heir, Nick Harkaway.

Sleeper Beach is the second of his Titanium Noir novels which, as the title implies, are taking the noir gumshoe pulps as their primary template. Our protagonist, Cal Sounder, is a private investigator with a smart mouth and a heart of gold, and as such gives Harkaway plenty of opportunities to have fun with the voice of the piece: the veiled threats and witty bravado of noir are all here, along with an element of self-deprecation that perhaps only an English writer could bring to the table, but Harkaway isn’t afraid to send up the form for its stereotypes and cliches, or to lighten a climactic fight seen with a pun so groan-inducing that Adam Roberts should probably think about putting a padlock on his notebooks.

But the Titanium Noir books are also science fiction, albeit in an interestingly subtle and low-key way. There’s a big obvious novum up front, in the form of T9, a drug that extends the lifespan of the super-wealthy at the cost (or perhaps the gain?) of increasing their size by around 20% each time they take it. This is a clear (and powerful) metaphor for the current socioeconomic circumstances, but rather than belabour that point, Harkaway just concretises it and goes to work on the implications. De-concretising them is for the most part left as an exercise for the reader—though while it’s a long (and merciful) way from being as politically on-the-nose as has lately become de rigeur in genre fiction, that exercise is not exactly cryptographic in its level of challenge.

I’m actually more interested in what’s behind the novum, though. That we’re in a future is evident, though aside from the T9, most of the evidence is subtle, and mentioned mostly in passing. In fact, what’s surprising is how familiar much of this future feels—human society hasn’t changed much at all, or so it seems. But details accumulate, and the sharp-eyed reader will have noticed that this is a climate-changed future: one in which literally lethal summer temperatures are so utterly normal as to go almost unremarked upon; one in which a formal fishing town, its old livelihood all but destroyed by shifting tides and other oceanic mishaps, is now economically dominated by a factory that turns trawled plastic trash into artificial flavourings to liven a much diminished array of food options.

It’s masterful worldbuilding technique: dripfeeding you the depth of field while you’re following the foreground action. But the world is itself interesting, too—like Harkaway set himself the challenge of exploring the timespace between today and the “jackpot” of Bill Gibson’s most recent work. In other words, he’s working within the short-to-medium-term futurity that hardly anyone touches these days without making it full-bore stereotypical cyberpunk dystopia… and that’s a trick few have tried, let alone pulled off.

a clipping

The ideal accompaniment to Harkaway’s novel is surely this essay by Roy Scranton, which takes on some uncomfortable environmental truths otherwise effaced by the well-intentioned discourses of postcolonialism and “becoming Indigenous”.

The peculiar character of our current impasse is that it is at once unprecedented, obscure, and banal as the weather. We face not a day of reckoning, but Apocalypse 24/7. Not a doomsday you can prep for, hack your way out of, or hide from, but your world dissolving around you. Not something with a beginning and end, but the prelude of a new form of life to come, which those of us alive today will never live to see: a promised land not of milk and honey but fire and flood, veiled in ashes and dust, more felt than seen.

(Long-time readers of my work may recognise Scranton’s argument as being a lot like my own argument for the inescapability of infrastructure, but approached from the other side, and much more willing to confront the academic orthodoxies rather than dance around them.)

ticked off

- Sixteen hours on PROJECT MALACHITE. (Two full days of facilitation at the Green Transition Hack, which was fun, but also absolutely exhausting for this confirmed introvert.)

- Nine hours on PROJECT FLATPACK. (Mostly report writing ahead of the first draft deadline.)

- Seven hours on PROJECT MORPHOSIS. (After the preponderance of report-writing in recent months, it’s really nice to be working on something where my contribution is pretty much pure fiction.)

- Three hours on these here weeknotes.

- Two hours of copyediting.

- Two hours of admyn. (I’m woefully behind on admyn, actually, but rest is also necessary.)

- Ten hours of undirected writing and reading, som vanligt.

Yeah, I have definitely earned a proper weekend, haven’t I?

And on that note, it’s time to meet a friend for coffee, so that’s your lot. I hope all is well with you, wherever you may be.

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 45 of 2025. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe. If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend who you think might also like it!

Comments ()