week 4 / 2026: baleen and blubber

Reading round-up: seeing monsters in the (geo)political mirror; the paradoxical essence of “community”; the enantiodromia of a far-right Euro-federalism; Melville's Moby Dick considered as science fiction.

“Waters of chaos / have invaded all space / the flood on earth again / I have to find the whales...”

This is WEEKNOTES at Worldbuilding Agency; welcome to newcomers and old hands alike.

OK, on with the show; click to skip to your favourite bits.

among the pixels

This week’s clippings have a fairly political flavour, which is perhaps not surprising given the tenor of the times. I want to start with an essay by one Richard David Hames, which starts with the widespread comparison of the US’s kidnapping of Maduro from Venezuela to what are assumed to be China’s ambitions for regime change in Taiwan. Along with much other Western chatter about China, Hames argues that this is not only historically ignorant, but revealing of a Western habit of projecting its own pathologies onto those it identifies as its opponents.

It would be convenient to say that Western misreadings of China are caused by ignorance. But that is only half‑true. There is no shortage of information about China. Diplomats, scholars, journalists, business leaders, and millions of Chinese citizens abroad offer a continuous stream of data and interpretation. The deeper problem is a refusal to let alternative categories of thought genuinely unsettle Western assumptions.

Hames is not playing apologist, here. Instead, he’s making a point that applies much more widely, but perhaps most urgently to the case with which his essay is concerned: the monsters we most fear are often our own faces seen in a mirror, and we would do well to actually attempt to understand those we assume to be our opponents.

A similar dynamic plays out a different scale in Agnieszka Pasieka’s exploration of what motivates young European far-Right activists. The simple answer is “community”, a concept also much lauded by activists on the left, but which is defined very differently by them.

But as Pasieka notes in her conclusion, while the content differs, there is a fundamental similarity to the form of this ideal, which is always “built on various forms of exclusion and construction of otherness”:

The communities that the critics of the far Right aspire to build seem so different – they are diverse, egalitarian, tolerant, cosmopolitan, LGBTQ+ friendly – that it might be hard to see any affinity between them, nor is it easy to entertain the idea that the drivers behind the community quest are similar. And yet, being frank about what they have in common is necessary for understanding what drives youth to embrace the often radical visions of community.

Again: monsters in the mirror. Last year I wrote a long piece for Vector, the critical journal of the British Science Fiction Association, which looked at this question in the context of a novel and a video game which both have “community” as their main thematic; in hindsight I can see that in writing it I was grasping toward something rather like Pasieka’s conclusion, as I tried to understand why the book felt like it was pushing me away, while the video game felt like it was welcoming me in.

If you’ve not done so already, I recommend reading Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger, which deals with this dynamic in detail and at length: taking one’s opponents for moral monstrosities seems mostly to ensure that they’ll do their best to live up to one’s expectations.

(Or, if you would prefer the one-line lay-daoist version, per Ursula le Guin: “how you play is what you get”.)

Talking of somewhat daoist perspectives, here’s the FT’s Janan Ganesh speculating that the European right might quite quickly become the most ardent advocates of a federal European Union. This seems absurd on its face, as he admits, but that’s a mark of how quickly things are changing, geopolitically speaking:

A hard-right euro-federalist: such a thing, you will say, makes sense on paper but not in real life, like a Penrose triangle. Well, a decade ago, it was just as hard to imagine a pro-Kremlin US Republican. Or even a highly protectionist one. It is possible for a movement to not just change its mind, but exactly reverse it.

I’m not sure I would be any more pleased to see that happen than would Ganesh, though our reasons are rather different. But the sense of multiple nested cases of enantiodromia unfolding at the same time is very hard to escape—and on that basis alone, it’s well worth considering that which mere months ago was all but inconceivable.

between the pages

This week I have been working my way through one of the canonical “great novels” that I’ve heretofore never gotten round to reading.

For most of my life as a reader, I’ve seen references and reflections on Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the vast majority of which have been at pains to emphasise its difficulty. This feels like it does the book a disservice: with the caveat that I’m currently around halfway through, which means that the novel still has room in which to prove me wrong, I wouldn’t say I’m finding it difficult. It’s slow going, certainly—though how much of that is a function of the rather more ornate written English of the mid-C19th, and how much is by contrast a function of Melville’s quick-change shifts of tone and genre from chapter to chapter, I couldn’t rightly say.

(I should also probably concede—I hope without conceit!—that I am probably not the average reader, and that both the language and the stylistic lurching might be considerably more difficult for the more casual consumer of fiction. But I think it’s good to read stuff that challenges you as a reader; that, after all, is how you get better at it.)

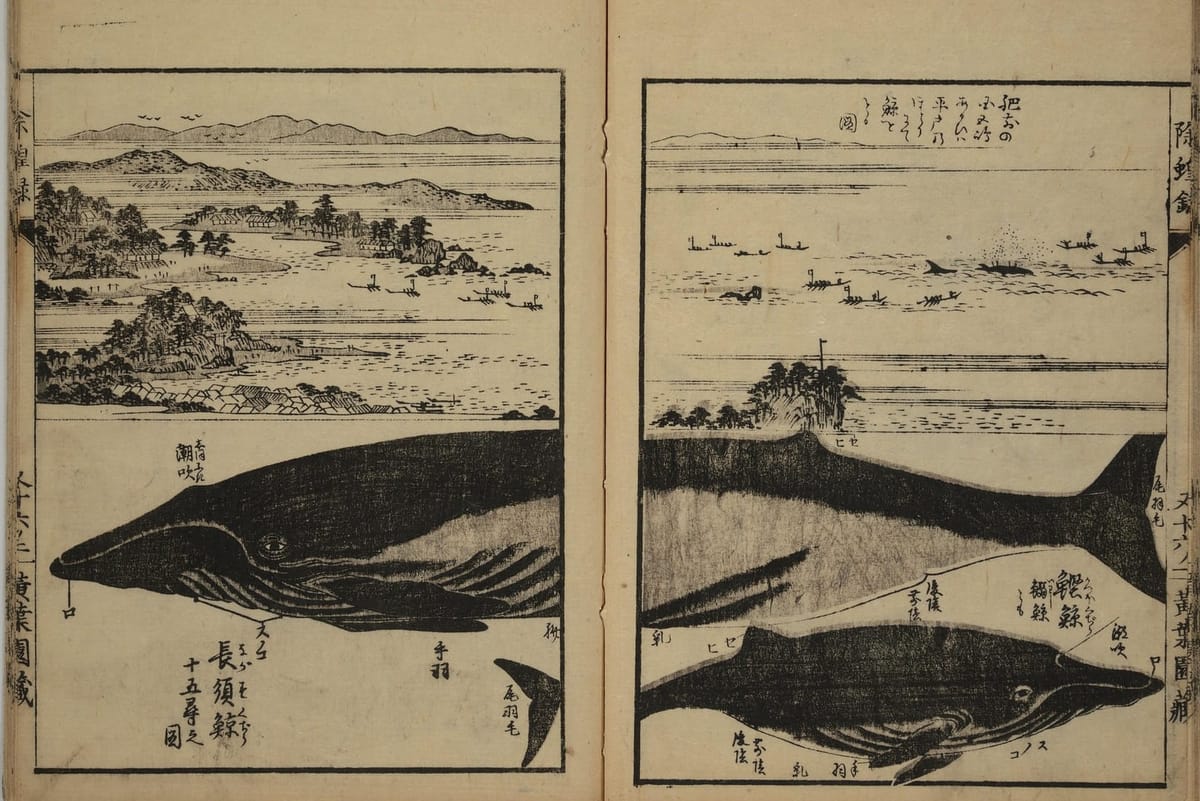

This is perhaps a classic case of seeing one’s own interests reflected by the art one encounters, but I’m finding myself developing an argument for Moby Dick as a sort of proto-science-fiction. Those shifts of genre and style are at least in part performative, the flamboyance of a master artist showing off their range; but I would argue that they’re also strategies to allow the extensive exposition necessary to unpack the world of whaling for a readership that likely knew little or nothing thereof. The echt genre of science fiction would, in the C20th, develop a whole bunch of narrative tools for drip-feeding such details to the reader, and that genre’s readership would in parallel develop the reading protocols necessary to decoding them; Melville had neither of these advantages, but nonetheless needed to deliver vast amounts of contextual material in a manner which would hopefully hold the reader’s attention. Indeed, I think I might even go so far as to suggest that the novel’s central story—Ahab’s doomed quest for revenge on the whale that relieved him of his lower leg—is mostly there to provide a through-line for the reader that will allow Melville to take them on a tour of the vast sociotechnical system that was the whaling industry of his era.

As is probably obvious, I could go on! But it seems a proper essay is taking shape on this topic, so I’ll keep my powder dry for that and share the results as a stand-alone piece. For now, suffice to say: if you’ve been putting off Moby Dick for fear of its difficulty, set aside your fears and get stuck in! For all its literary repute, its worthiness and its thematic seriousness and its linguistic density, if you were to force me to describe it with just one adjective, that word would be hilarious.

lookback

This week has been dominated by my teaching the inaugural run of my Fiction4Foresight course, which went really well. My participants brought a real commitment and a very respectable level of raw talent to the sessions, and entered properly into the spirit of workshopping which—while not without its shortcomings—is a central plank of almost every framework of teaching fiction writing for very good reason.

As someone who did a practice-based Masters in creative writing, it was very interesting for me to see this from the other side of the pedagogical fence. As a relative beginner in the writing of fiction, one finds oneself desperate for plain and direct instruction: how best to describe a scene, how to make dialogue work well, etc etc. There is no shortage of simple answers to these questions, either, and they are for the most part provided with the best of intentions—but as one continues to develop, one starts to realise that homilies you took to be rules (such as “show, don’t tell”) are really rules-of-thumb at best, and misleading heuristics at worst.

This is true in almost any field of endeavour, of course, not just in storytelling; the aphorisms endure because there is something of value in them. “Show, don’t tell” is a great example, and also illustrative of the value of the workshop method: put as simply as possible, it’s extremely hard to explain “show, don’t tell” as a general proposition, but very easy to illustrate it with specific examples of showing (or its lack) in a text that the whole group is discussing.

My participants tell me they learned a lot, and I learned a lot as well: you gain a new perspective on your practice when you attempt to teach it! It was well enough received, and fun enough to run, that I will definitely be teaching more such courses in times to come—and aiming to make them more accessible, whether in-person or online. Stay tuned for more details, wot?

ticked off

- Twenty-four hours of teaching. (See above! Three eight-hour days on the trot is a lot… though my workload was most intense around the beginning, while the workload of the participants increases toward the end, with the last day being almost entirely devoted to just blasting out a draft story.)

- Seven hours of admyn. (Bits, bobs. The Swedish accounting year turns with the calendar year, so January is all about getting your financial ducks in a row—or rather having your accountant check their alignment before filing the pertinent declarations.)

- Three hours on these here weeknotes.

- Three hours of art practice.

- Two hours of reading for research.

And the traditional ten hours of undirected writing and reading, which is the infrastructural habit that makes all the other stuff possible.

That’s all from me for this week. Do please pipe up (whether by replying to the email version, or commenting on the site) with any good reads of your own you have to recommend, whether online or off! In the meantime, I hope all is well with you, wherever you may be.

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 04 of 2026. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe. If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend!

Comments ()