week 36 / 2025: at the intersection of three things

I've been going on about this "narrative prototyping" thing for ages now, but how does it differ from science fiction and/or design fiction? Well, since you asked...

“And the old man is down by the river / well he gets up, and he walks on down / to the spaceship that's parked at your doorstep / and it's waiting to take you away, now...”

September. September?!

September! From the look of the forecast, the warmth of summer will linger a while yet here in Malmö, but the mornings are starting to acquire a hint of that cool autumnal crispness, and the days are shortening fast. I think of summer as “my season”, but autumn comes with a sense of rebooting and purpose which, I assume, comes from the influence of the school and academic calendar. As I said to friend-of-the-show Reeta Hafner last week, we have a ceremonial new year when December gives way to January, but this is the functional new year—a time for buying new stationery, whether figuratively or literally. (Or, if you’re me, both; it doesn't take much to make me buy new notebooks.)

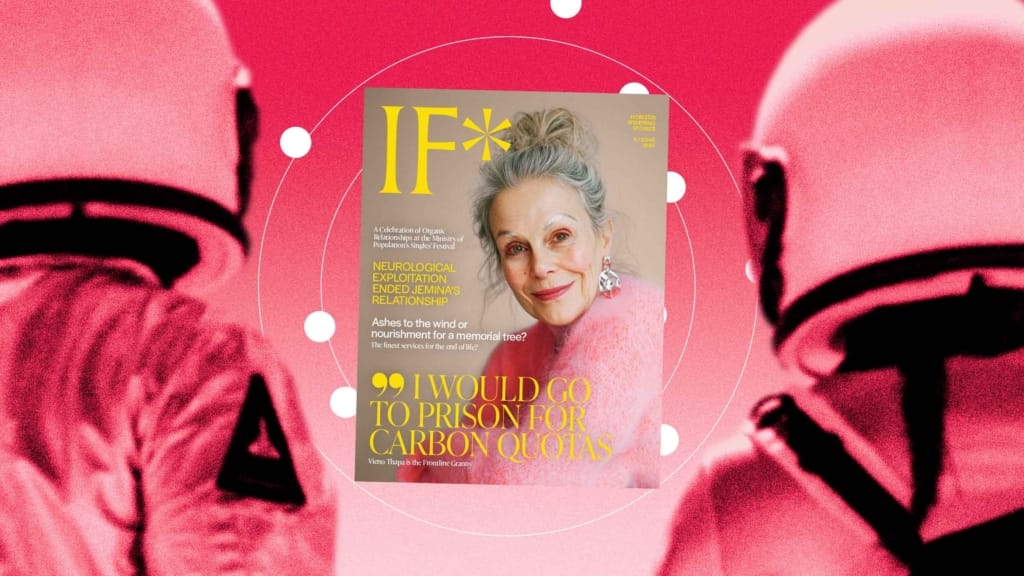

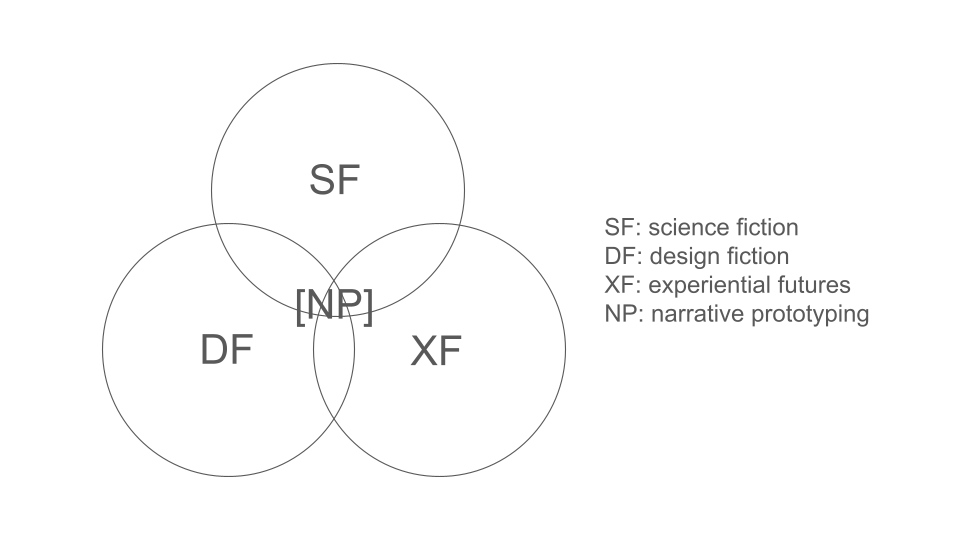

It’s also a time for reassessing what you do, and why. Regular heads at Worldbuilding Agency will be aware that I describe my favoured futuring practice as narrative prototyping, because there’s a sense in which it is distinct from both science fiction and design fiction, although it uses techniques and approaches drawn from both. I’ve been poking at the distinction from science fiction in recent weeks, but this week I want to switch modes and look instead at the distinction from design fiction—a decision prompted in part by Sitra’s excellent 2025 weak signals publication, IF*.

Sitra describe IF* as follows:

The 2025 edition of the Weak Signals publication, presented as a fictional issue of IF* magazine [set in 2046], brings a range of possible futures to life. The stories are speculative glimpses into different futures, with each being grounded in real-world weak signals: events and phenomena that have already occurred somewhere.

Now, I’ve worked on a number of “future periodical” projects; the most relevant comparison here is probably the “jubilee” issue of LUM that I worked on when I was still at Lund University, but the Chronoberg Chronicle is also relevant (despite some differences, which I’ll discuss another time). But I think of these projects as narrative prototyping, while I think of Sitra’s IF* as design fiction.

To be very clear: this is definitely not a diss or a value judgement! IF* is a very classy piece of work: at a technical level, it does much more than merely list a batch of weak signals, and in doing so it packages the work in an eye-catching way that sets it aside from the flood of more “trad” foresight reports. I commend it to your attention.

I also invite you to notice what it’s not doing. This is no revelation on my part, either, as Sitra are very upfront about it:

Rather than outlining a single scenario, the magazine offers snapshots of diverse potential futures.

IF* is presenting multiple fragmentary futures, united only by a two-decade temporal horizon and their being collected in this magazine. In other words, it is not presenting a single future, a coherent world.

If anyone gets to define what design fiction is for, it’s Julian Bleecker. In a recent interview, he says that it’s

about making something tangible that acts as a “prop” for a possible future. The goal is to place it in front of someone to transport them to a different timeline, so they can understand what a possible future with that artifact could exist and by extension what that world could feel and look like.

My gloss on that and other statements would be that it’s a starter for a conversation; the design-y part of the process is not inconsequential, by any means, but the artefact is a quick (and sometimes dirty) doorway to a possible world which, quite deliberately, remains underdetermined. The exploration comes later, when that door is opened by someone who encounters the artefact

As such, I see IF* as being a collection of design fictions: a corridor of doorways, if you like. But that corridor exists between those possible worlds; it is not a world in itself.

This, I think, is the distinction of what I call narrative prototyping. Like IF*, a narrative prototype uses a media-artefact format (e.g. a magazine or periodical) as a container for little design fictions, but all of those fictions are from the same world.

Put another way: design fictions are an invitation to an exploration of a world, but a narrative prototype is an exploration of a world. A narrative prototype goes deep, gets into the corners; it’s more sustained. As such, I think I will start positioning it at the intersection of not just science fiction and design fiction, but also of experiential futures: narrative prototyping is more immersive in its attempt to bring that future to life.

This is not a claim for methodological superiority, to be clear. You might well argue that the underdeterminedness of a simple design fiction leaves more space for its audience to do their own exploring, and I would agree; in the terms of my own theoretical framework, such artefacts are doorways to worlds that are radically open, while a narrative prototype closes its world somewhat in the process of exploring it in greater detail.

My storying work, in which I take scenarios and write short fictions set in the worlds they describe, definitely works as a closing of the futures in question. It is not, I hope, a complete closing! But the process of concretisation undoubtedly reduces the imaginative space, because I am filling that space with my imagination. And here we should recall the relationship between the words author and authority: my role as translator of abstract scenario to concretised fiction is necessarily solo and autonomous, which gives me a tremendous power of influence over the result. I do my utmost to use this power responsibly, and to honour the material I’m given to work with; indeed, that’s one reason why I mostly stick to observer-only status in the workshops that produce the scenarios I get to storify.

But while it benefits very strongly from having a singular someone in what is essentially the editorial role, a good narrative prototype should emerge from a collaborative process of exploration. Yes, it closes down some of the openness that accrues to a pure design fiction artefact—but what’s happening here is a concretisation and capture of the process of exploration, rather than its foreclosure. The design fiction artefact represents the potential for exploration; the narrative prototype documents that exploration, and makes it available to others.

Again, this is undeniably a closure of sorts—but I would argue that the movement of concretisation, which is also necessarily a movement of subjectification, actually provides a different sort of openness. The narrative prototype might be seen as collapsing the wave-function of speculation down to a single possible world, but any single possible world will contain an almost uncountable number of different perspectives. A single world is still a plural world, full of conflicts and contradictions. Closure of breadth is the price for the opening of depth, and vice versa.

So there’s the distinction, perhaps, between design fiction and narrative prototyping: design fiction enables and emphasises the parallel plurality of futures, the broad spread of possible worlds, while narrative prototyping enables and emphasises the singular plurality of futures. Neither is “better”; they’re just different means to different ends.

Indeed, I think they’re highly complementary—but that’s a discussion for another day.

reading

Reading the introduction of my Penguin Classic edition, it would seem that Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia was received by the literary world in much the same way as the music world received punk rock at around the same time: it divided opinion, but the sense that something new had arrived seemed fairly widespread.

In further keeping with that analogy, In Patagonia was nowhere near so radical as some made it out to be—a point that its author was at pains to have pointed out in later editions. From my vantage, reading it for the first time nearly half a century after it was written, it’s not particularly shocking in terms of its form, which I must presume has influenced a great deal of non-fiction written since—an influence which I have presumably absorbed as normative. It’s mosaic travel writing, basically, that eschews a linear narrative structure and ostensibly occludes its author/narrator—though as the introductory essay notes, Chatwin-as-character is an absent presence, a haunting clearly felt. (And not always entirely agreeably, if I’m honest.)

It’s OK? I mean, I’m enjoying it enough to have motored through most of it in a few evenings, but I don’t think it’s going to end up as an important part of my personal canon.

a clipping

Yep, it’s another Aeon joint—what can I say? They’re one of the most reliably interesting online essay sites, and have been for a decade or more. No apologies, then, for clipping this piece from Philip Ball on what he’s calling “oneiric technologies”:

These are not simply technologies of the future that we don’t yet have the means to realise, like the super-advanced technologies that Arthur C Clarke said we would be unable to distinguish from magic. Rather, oneiric technology takes a wish (or a terror) and clothes it in what looks like scientific raiment so that the uninitiated onlooker, and perhaps the dreamer, can no longer tell it apart from what is genuinely on the verge of the possible. Perpetual motion is one of the oldest oneiric technologies, although only since the 19th century have we known why it won’t work (this knowledge doesn’t discourage modern attempts, for example by allegedly exploiting the ‘quantum vacuum’); anti-gravity shielding is probably another.

It’s a good piece, and I’ve always got shelf-space for people pointing out the fantasist delusions of the “men of science” (read as: engineers with a chip on their shoulder) who have traded on false futurities to ascend to positions of power in the present.

That said, I’m a little sad that the term “oneiric technologies” will henceforth refer to “technologies that could only work in dreams” rather than “technologies of dreams and dreaming”. The latter would have made a rather nice label for the triad of imaginative methods discussed above, don’t you think?

ticked off

- Ten hours on PROJECT FLATPACK. (Expert interviews are honestly one of the most delightful parts of foresight research. Who wouldn’t want to get paid to ask brilliant people to explain fascinating topics?)

- Ten hours of admyn. (Various and sundry things, by definition, though a lot of out-of-office run-around stuff this week, the reason for which I will reveal in the next episode. I know, I know, I’m such a tease!)

- Six hours on PROJECT PORTON. (Edits, edits, more edits. It ain’t glamorous, but it’s where quality comes from.)

- Four hours of kinmaking. (See below; figured this should be ledgered as well as detailed.)

- Four hours of research. (Directed, but not yet project-specific; hence the separate ledger entry.)

- Two hours on PROJECT LYNCH. (mister-burns-steepled-fingers-excellent.gif)

- Ten hours of undirected writing and reading.

Busy week! It’s that back-to-school vibe, innit?

kinmaking

The 2025-6 season of Malmö Futures Folk is up and running after Wednesday’s inaugural meet-up. The October date is already set: 08:30am on Wednesday 8th at Ruth’s. If you’re in the area, do feel free to drop in, we’d love to meet you!

I had a nice chat with Frank Spencer of TFSX on Thursday evening, themes from which contributed a fair bit to the essay above—thanks, Frank!

I also caught up with Richard Sandford, who’s currently doing some time at CESR as well as his regular UCL gig. Always a pleasure to spend some time with people who enjoy digging into the theoretical side of things… though really we spent a lot of this call just generally shooting the shit, which is a different but equal pleasure.

OK, there we go—a long weeknotes for a long week. I hope all’s well with you, wherever you may be.

Comments ()