week 31 / 2025: churches of futurity

What can we learn about futures from thinking about them as if they were faiths or fandoms? Quite a lot, if you ask me...

“I'm on the wire, over and higher / over the pretence, over the spire / on and connected / I'm overfloating now...”

First of all, thanks to everyone who wrote in to request a tarot-for-strategy reading off the back of last week’s post. The five slots are accounted for now, with a few reserve places in waiting. I’ll report back on how they go (without exposing any personal or sensitive details, of course).

This week I want to return to an earlier theme, namely the utility of media fandoms as a model for thinking about how people relate to futures.

It feels like a long time since I last decided to start a blog post with an XKCD cartoon. Two decades ago, it was almost a standard strategy!

Why am I sharing this? Because it sidles up to a point I made here a little while back, in an essay titled “nowhere to go but further in”: that media fandoms are best thought of as being less dedicated to stories that to the worlds that those stories imply. Given that worlds are always more implied than they are described, we can say further that fandom disputes—canon wars—are ontological arguments about the world in question, they are attempts to express values and ideals through the ordering of a reality.

Now, “reality” is an admittedly vexed term in this context, even if I qualify it with “imaginary”. But I think it suffices to observe that, for a fandom, the world to which it is dedicated is intensely real, because of the extent to which it matters. Indeed, it may well be more real to them than the “reality” described by empirical science—which is, in a sense, also a world that has been narrated into reality, albeit through a very specific set of narratological devices, perspectives and conventions.

I’m sure at least some of you are at this point muttering something along the lines of “postmodern relativism”, but I counter any such accusation with Latour’s retort: we have never been modern. If the suggestion that science, broadly conceived—which is to say, conceived as it is by most people who are not themselves scientists—might work in a way analogous to schismatic faiths and/or media fandoms is too spicy, perhaps you would find it easier to accept that modernity works this way?

Or, more accurately, that modernity has worked this way. One useful way of looking at the prevailing epistemological circumstances is exactly as a canon struggle over what it means to be modern—a struggle in which a number of intense contradictions, both physical and philosophical, have led swathes of former adherents into schism, or even to full auto-excommunication; accusations of heresy and claims to be the bearers of the One True Interpretation inevitably follow, as do the conflicts that characterise the collision of absolutist and fundamentalist worldviews. “This town ain’t big enough for the both of us,” and all that.

Now, modernity is a story about how things are, but it is also—sometimes quite explicitly—a story about how things will be. To put it another way, modernity implies a future, and always has done. (It also implies a history, which is in many ways just as speculative.) Putting that into our analogical terms, then, being a “fan” of modernity means signing up to a particular narrative of futurity. To be very reductive, this is the narrative that is folded into the deceptively simple label of Progress; it’s the sociotechnical version of our old economic friend “number go up”.

This doctrine still has many adherents, particularly in important western institutions, though their influence (and the doctrine’s power) have been dwindling for some time: an illustrative example would be the discourse around Klein and Thompson’s Abundance, a text which we might take as marking the orthodox center of the current liberal-modernist faith.

It’s a cliché of foresight to note that “futures are plural”, but there are (at least) two claims contained in that phrase, one of which is more explicitly acknowledged than the other. The more commonly expressed meaning is the one that talks to possibility, to the openness of futurity: “futures are plural” means “many different worlds are possible”. However, the other meaning is actually focussed more in the present: “futures are plural” also means “there exist many different ideas about what futures are desirable”.

The latter claim is less discussed, I suspect, because it emphasises the normative function of narratives of futurity: they are statements of ideals and values, arguments about how things should be in times to come. In other words, narratives of futurity are necessarily and inescapably political. This is uncomfortable for some practitioners, for whom politics is a messy distraction from the exigencies of business, both theirs and that of their clients. But as has been pointed out by many people, all of them far smarter than me, any claim to be “above” or “beyond” politics is always a tacit admission to being fairly well-served by the political status quo.

So, futures are plural—and many of them are just minor variants on the doctrine of modernity already discussed, which is in turn the reality which still just about passes for The Reality. But, as already noted, the church of modernity has been haemorrhaging congregation for quite a while: its promises have fallen short, and its priests have been caught in acts of hypocrisy. The future implicit in modernity’s worldview just isn’t as convincing as it once was.

One of the prevailing ways of talking about this exodus, and of trying to stem the tide, is to talk in terms of deceit and misinformation: folk are turning their backs on modernity, the moderns will tell you, because assorted pied pipers have seduced them away with false promises. That may be more or less true, as it stands—though that’s a big discussion in its own right—but even so, it’s only half of the picture: to be seduced away by new promises, you must have lost your faith in the old ones.

This is why I’ve been saying for a while that fandoms provide a useful model for thinking about the micro-scale politics of futures. First and foremost, it ascribes equal importance and agency to both the narrative and its fans, where most theories tend to focus on one to the exclusion of the other. Secondly, it makes explicit a point that bubbles up more frequently on the more creative fringes of foresight practice: that futures are plural, yes, but that they are as such also contested—and that this contestation is, on balance, a good thing.

reading

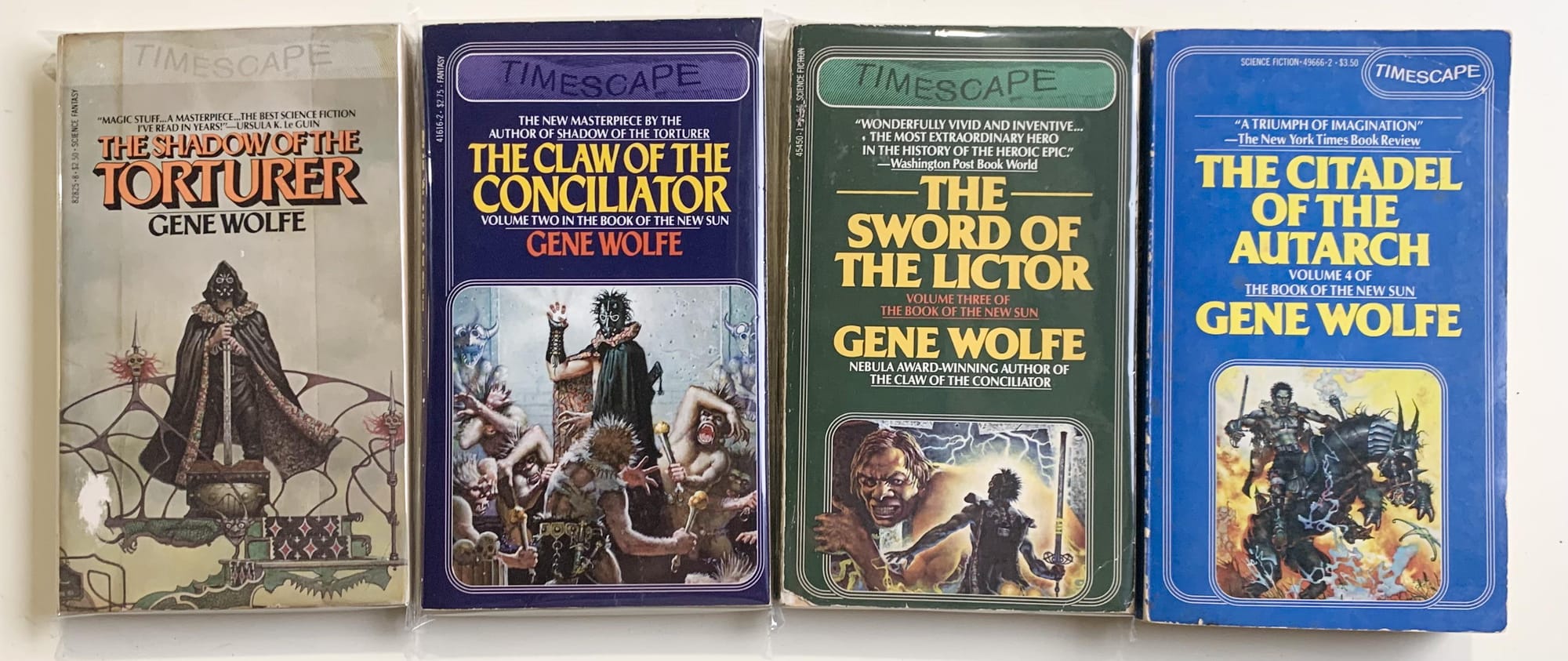

This week I have been ploughing my way through Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun sequence, which is resistant to summary, and even to accurate description: my best one-line approximation would be to call it a philosophical-theological science-fantasy fever-dream Pilgrim’s Progress, a crypto-Catholic dying-Earth ideas-adventure of staggering strangeness, horror and beauty.

I bounced off it about half-way through on my first read, which I put down to my own philosophical inclinations at the time being too rigidly New Atheistic; I even wrote in a review at the time (perhaps two decades ago?) that I felt I was being proselytised to, which may not have been entirely inaccurate. I guess the difference now is captured somewhat in my discussion above: I’m more willing to encounter the doctrines of others on their own terms than I once was.

While I don’t recommend that you should expect my conversion to Catholicism any time soon, Wolfe’s ability to make strange the tenets of that faith by displacing them into a far future—tenets which, it bears noting, are deeply strange to start with, in a way that it’s easy to overlook—demonstrates not just the capacity of fiction for exploring difficult ideas, but also Wolfe’s extraordinary command of image and metaphor. It’s not an easy series of books, nor a small one—the omnibus edition I’m reading clocks in just short of a thousand pages—but this time round, I’m finding the journey hugely rewarding.

a clipping

This week’s clipping comes from design provocateur Silvio Lorusso, and echoes an argument I’ve been making for a while now, which boils down to “the claim of bad-faith argumentation is itself a bad-faith argument”:

It’s time to realize that we live in a Machiavellian world of deceit and lies (including the lies we tell ourselves), where even a display of kindness can lead to harmful outcomes. Let’s finally admit that our good intentions have helped pave the road to the hell we now find ourselves in. Signaling virtues in public, whether professional or moral, is self-defeating. Let’s stop asking whether something is performative, whether someone is sincere. Instead, let’s assume (like Wikipedia editors do) “good faith”: I know you care, no need to point that out. But if you point that out, I will look at your intentions as actions, and evaluate them by their effects. We’d do well to remember Stafford Beer’s words: “The purpose of a system is what it does”, not what it claims to do. Claims themselves are part of the system, and they can just as easily produce the opposite of what they assert.

ticked off

- Thirteen hours on PROJECT FLATPACK. (Research, which is always fun; spreadsheets, which are, uh, rather less so. The rough with the smooth, and all that jazz.)

- Ten hours of admyn. (Including a bunch of roughing-out on a potential project bid, the prospect of which arose fairly unexpectedly. We’ll see what comes of this one.)

- Eight hours on PROJECT PONTIF. (PONTIF has suffered once again from other things cropping up to get in the way—see above. I need to do a better job of protecting my time for this thing than I have this week.)

- Ten hours of undirected writing and reading, as always.

- Plus two hours in an online masterclass on the topic of selling foresight services. (This was actually more useful than I had expected; whether the learning will be easy to apply is another question entirely, of course.)

kinmaking

No kinmaking this week. Normal people are on holiday. :)

OK, that’s everything for this week. I hope all’s well with you, wherever you may be.

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 31 of 2025. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe. If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend who you think might also like it!

Comments ()