week 27 / 2025: on models and literacies

"All models are wrong, but some models are useful"—so the saying goes. But how are they wrong, and how are they useful? And what does that mean for thinking about futures?

“When it happens, you'll feel like an islander / you'll see WEEKNOTES and they'll be reminders / that you're on an island...”

I doubt many of you will be surprised as I reveal that PROJECT PONTIF is a book project, albeit one that is only at the proposal stage. In it, I hope to bring together much of my work and thinking about futures from the last fifteen years or so.

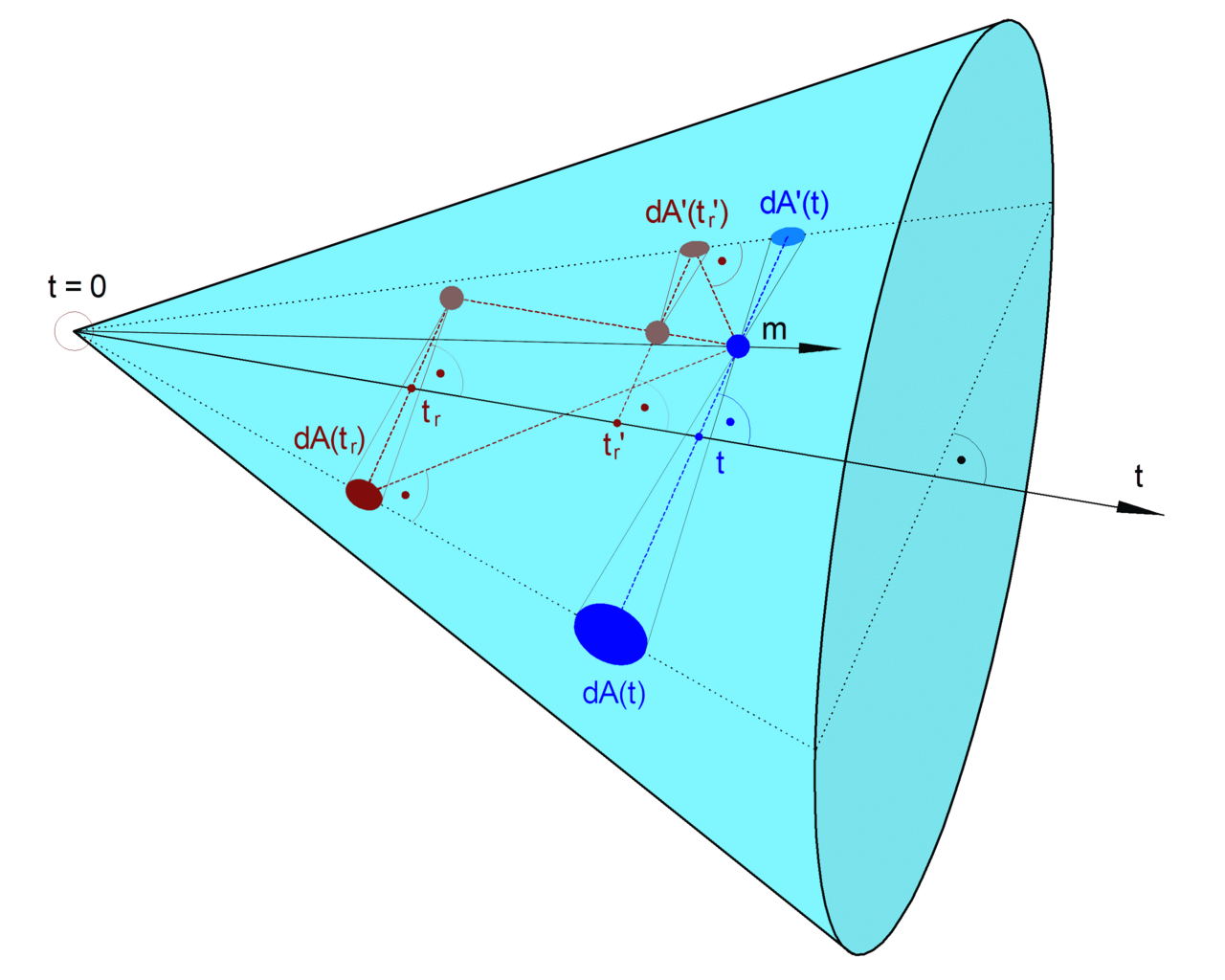

My current plan is to start with our old and controversial friend, the futures cone. There have been plentiful critiques of the cone since its popularisation by Joseph Voros, as well as counter-proposals, remixes and extensions of it. This is, I think, a sign of conceptual health in the field, as well as an illustration of a deservedly famed aphorism from the late statistician George Box, which is much beloved in the circles wherein I tend to move: “all models are wrong, but some models are useful”.

The hazard of thinking with models is best summed up by Korzybski’s observation that “the map is not the territory”, which reminds us that, however thoroughly we might attempt to model the world, we necessarily relegate some of it—maybe even much of it—to context. In other words, we externalise: this is explicit in the operation of a scientific laboratory, where the exclusion of multiple variables allows the focussed examination of just one or two, but it’s also fundamental to orthodox economic thinking, in which costs that cannot easily be represented in terms of money (pollution, for instance) are effectively excluded from the ledger.

Thinking with models is very powerful, as demonstrated by the power of the scientific method. It is also dangerous, as illustrated by the problem of climate change.

At its best, futures work tends to makes use of the movement between the abstraction of model-based thinking and the concrete reality of the world of experience. Perhaps that’s why so much futures practice is about process? (I’m thinking now of John Willshire’s Three Future Frames device—not yet available online, to the best of my knowledge—which makes explicit this movement between different scales of conceptualisation of an imagined future.)

Why is this movement necessary? Because abstract thinking is an acquired skill. I believe that the vast majority of people are quite capable of it, but it requires training and practice—it’s a mental muscle, if you like, that needs to be exercised. Those of us who have undergone advanced levels of education have had that training; those of us who work with abstract ideas have had the experience. I suppose we could describe it as a form of privilege, though perhaps it would be fairer to call it an acquired advantage.

Here we encounter the root of my enduring beef with the futures literacy paradigm (FL), which starts from the idea of “poverty of imagination”: if only we could teach people to think further ahead, all our problems would be solved! As I have remarked many times, I believe FL to be motivated by the very best of intentions, but it is also coming from a place where abstract thinking is a largely unquestioned norm. The problem with FL, then, is its “imagination of poverty”. It’s not that ordinary people aren’t capable of imagining futures; rather, it’s that their imaginations are constrained by their circumstances. It’s hard to think about the possible fates of humanity thirty years hence when you’re preoccupied with the possible fate of your bank balance at the end of the month. (Ask me how I know!)

This is a big part of why I think narrative and creative approaches to futuring are so important. They are a way of taking the abstractions of a scenario and making them concrete and relatable; they are a way of meeting people where they are, and letting them enter and explore futurity.

Of course, there’s a sense in which any imagined future, no matter how concretely brought to life, is itself also a sort of model. However, it’s a sort of model that relies not on the specialist skill of abstraction, but rather on the ability to parse narratives, to understand stories—and that, as I will never tire of repeating, is the literacy that precedes literacy. It’s as close to a universal human capacity as we’ll ever get.

This narratological literacy comes with a tacit understanding that stories are partial, in both senses of that term: necessarily incomplete, and shaped by the subjective position of their narrator. In other words, we already have an instinctive understanding of Box’s observation about models, as applied to one particular sort of model, namely the story.

But that’s not quite right, because “story” is not a sub-category of “model”. It’s actually the other way around: “model” is a subcategory of “story”, and that’s why one of the big through-lines of my book will be an attempt to show that relationship in an accessible and useful way.

How might we build on that innate knack for narrative? How might we use creative techniques of futuring to get people in on the ground floor, and so allow them to not only enter and explore imagined futures, but to critique them and propose their own?

That, it seems to me, is a literacy worth working for.

reading

This week I wolfed down Margaret Atwood’s Cat’s Eye, the latest selection for our local book group. I will refrain from summary, and limit my rhapsodising to the simple statement that it’s one of the most brilliant and moving literary novels that I have ever read. Sincerely recommended.

I also finished Richard Cohen’s Making History, which I’ve been chipping away at for close to a month. It’s a work of metahistory, in essence: Cohen follows the formation of history as a literary mode and an academic discipline by looking at the authors who wrote it, starting with the ancient Greeks, Tacitus and Herodotus, and ending with the television historians of the current age.

The whole book is animated by the tension between objective accuracy and narrative vigour, which it is tempting to assume is a very contemporary concern, but—as Cohen shows—it has always been there, right from the start. Like the historians he profiles, Cohen comes to the work with his own biases—as do we all! This is less obvious when he deals with periods at a greater temporal distance, but becomes a little grating toward the end, where his closeness to the characters he’s talking about—who, he reveals, were also asked for feedback on the material dealing with them—makes the final couple of chapters feel rather too chummy for comfort.

Nonetheless, as an overview of the field, and as a sketch of (mostly Western) history in and of itself, I’ve found it very engaging. Cohen is definitely more on Team Herodotus, in that he’s fond of dropping tangential asides into his copious footnotes; some of these have more than a hint of the dad joke about them, but I guess I’d rather have dad jokes than none at all.

a clipping

Henry Farrell has been dropping a lot of material lately that is of fairly direct relevance to PROJECT PONTIF. Here he is referencing not just Gibson but Ballard in a discussion of Adam Becker’s recently published More Everything Forever (which is a new addition to the heaving list of books I need to acquire):

In retrospect, it isn’t surprising that science fiction merges into technocracy which in turn merges into techbro exhortations. All are narratives of technological enthusiasm, depicting a future in which the engineers have taken charge, and in which innovation is a fountain of boundless possibilities.

ticked off

I’ve been taking it a bit easy on the work front this week, not least so as to take advantage of the fantastic weather, but also because I kinda needed a bit of a break.

- Eight hours on PROJECT PONTIF. (Including an unexpected spin-off essay which I’m hoping to finish and publish here next week.)

- Seven hours on a one-off proofreading job. (If you’ve got an academic publication that needs a polish, whether at the level of sentences or of structure—or both!—our operators are waiting for your call.)

- Twelve hours of admyn. (Much of this involved cleaning up the task-management system after a few months of under-maintenance, and planning out how to get the best use out of the summer lull.)

- Ten hours of undirected writing and reading.

kinmaking

Had a nice catch-up chat with Andrew Curry of SOIF on Tuesday. (You have him to thank—or perhaps to blame?—for my decision to unmask PROJECT PORTON and start writing about bits of it here in WEEKNOTES.)

I also took the whole of Wednesday off to spend some time with Christine Prefontaine and her partner, who were in town for the week. In keeping with the somewhat historical bent of the week, we went to visit Bosjökloster, a former abbey on the shore of Ringsjön in central Skåne; a lovely day out, in marvellous company.

That’s all for this week. Maybe you'd like to let me know whether you’ve enjoyed this little peek at PROJECT PONTIF, or what you’ve been reading lately?

This has been the Worldbuilding Agency weeknotes for Week 27 of 2025. Thanks for reading! If you've enjoyed them, it's free to subscribe. If you are already subscribed, please send to a friend who you think might also like it!

Comments ()