unknown pleasures: an interview with Cameron Tonkinwise (part 2)

In the second part of my interview with Cameron Tonkinwise, we discuss Transition Design, prefigurative politics, dramaturgy, narratology, imagination, and... urban cycling as filtered through the philosophy of Georges Bataille?

Welcome back to Worldbuilding Agency for the second part of my interview with design philosopher Cameron Tonkinwise. You may want to revisit the first part, as we're continuing straight on, in medias res, so to speak.

In this section, Cameron introduces Transition Design, a fundamentally prefigurative approach to futuring in which the goal is less about assembling a utopian destination and more about finding ways to manifest different possible futures in the present, if only partially, and to protect their expression for long enough to let them grow.

We then move on to the dramaturgy and narratology, the ways in which those frameworks can get us to a similarly prefigurative conception of futuring, and specific techniques and approaches to design and storytelling which can provide that sense of depth and versimilitude, and the cognition-bending magic of Marcel Proust.

From there, we're into the latency of suppressed imagination, and the true challenge of Transition Design, which is to get people to imagine themselves as different people with different pleasures. We round things up with a discussion of the affordances for futuring work of different media, and the possibility of looking to the past---and, perhaps, to Ursula e Guin and philosophers of cycling?---for pieces of the puzzle.

If you're anything at all like me, you're gonna end up with a whole list of books to acquire by the time you get to the end of this one!

Cameron Tonkinwise: I have got hundreds of things to say, because [Vitiden, as discussed in the first part of the interview] was really interesting and important, and goes to questions of design and futuring, and to the separate project of Transition Design—which to some extent bridges them, but to another extent I would actually characterise as something completely different.

Let’s say there is the future and the present. There is always this debate, why are we doing futuring? Are we doing futuring to actually predict or normatively decide what the future is? Or is futuring just a game to change the present?

I worked with Jabe Bloom, who is a really interesting ex-technology-officer, and his PhD was on what he called Temporally Informed Designing. He is very insistent on the futuring part of designing being entirely about the present condition; ‘futures’ are just another thing in the present that might change the present. If you design or ‘worldbuild’ some attractive future, the common ‘theory of change’ is that you are making a future to head toward. But that is still at the imagination-ideas level. It is not enough to help people imagine, though there is certainly a poverty of imagination—an inability to see, as Graeber puts it, that the world is made, and so we could make many other different worlds.

But those alternative worlds we fiction are going to be a dream, quite literally—in the sense of a thing that you are going to find hard to hold on to. Even if there is an artefact from the future sitting in a gallery somewhere, when you are not in the presence of it, it is going to disappear. The agency of some attractive future is more about someone reflecting about the present, “shit, why is it this way? It could be another way, there were all these other ways in the past...” The Tony Fry project of ontological design and redirection is, in that Jabe Bloom sense, about changing the present.

This is what Transition Design is actually about. Though ‘vision-led,’ it isn’t just coming up with an attractor in the future; the whole job of backcasting, the actual design choices you make after doing Transition Design work, is to work out what version of the future you could actually start practicing here and now in the present. It is not that the future changes the present merely by being there, as an artifact that people can imagine, even if an artifact that is attractive. It is actually the project of prefigurative politics, which is to make an instance of the future now—and to protect it.

Transition Management people use jargony phrases like ‘sociotechnical bounded experiments:’ you have to create niches that protect that cultivation of this new bacteria. You get people to actually live in that futural way in the present—like intentional communities, but not at the full level of the community, of course: it could just be new ways of working, new types of offices, different types of kitchens, pieces that are decarbonized. And you are going to have to work really hard to ‘hold space’ for those cultivating experiments, which means you are going to have to do a whole bunch of defensive design compromises with the present. The point is: you have to hold open that space right now—and your version of what you envisioned is going to be really inadequate, because all you are doing is just trying to protect it, so it’s no longer just the attraction version; it is the pre-figurative changing of the present.

Now, all of this stuff I’ve said: future, present, attractor and pre-figurative. I think all of that is interesting to put into your language of world and story and text, because different levels of materializing different things will do different things in the whole narratology setup that you depicted as nested boxes. Some of what a transition design might materialise makes the vision look different from the present; another makes the vision look plausible; other things allow people in the present to try out the vision, practice it; others defend it from being overwhelmed by present values. All this—apart from perhaps that last one—has been recognized by the ‘design fiction’ crowd. Another way to talk about this, which picks up your talk of the craft details of narratology, is to think about worldbuilding in terms of what is in the foreground or background, and of levels of completion and incompletion at different levels of the world.

[Going back to what you were saying about Vitiden], if people have to do some work, like you show them the menu: you don’t do the whole world, you don’t even do the whole story, but you do enough to make them participate in the construction of the world. And if they are participating, they are doing a bit of prefigurative worldbuilding themselves! Materializing embodies the process in that kind of way. Incompletion is a really important point. Books that are oversaturated in their worldbuilding aren’t interesting; to my mind it’s kind of Asimov. I’m really thinking of David Mamet’s advice that you must start every scene late and leave it early: you come right into the middle of the argument, and you leave before it’s resolved. That’s drama.

I’m always telling designers, you’re not just designing one thing and hoping the world of the gerund, the social practice timespace, materializes automatically in the background. You have to choose carefully at least two things, so that someone looking at it is trying to work out what’s going on between them. “What’s this? Oh, I can see—now I’m in it…” Not everything is resolved; it’s not a utopia, some challenges are solved, but there’s still lots more to do.

PGR: At least at a lip service level, most of the futures world nowadays would say “oh, no, it’s not about prediction,” but I think a lot of people would still talk about an orientation towards the future. In one of my standard presentation riffs, I start off by saying, look: ‘The Future’ is dead. But when I say ‘The Future’, it’s in scare quotes, and it’s capital T, capital F, right? Because that C20th holidays-on-the-moon shit, that’s over. It’s gone. But one of the reasons we’re in such a mess now is because we’re mourning the loss of that, but they just keep propping the corpse of The Future up in front of us.

So for me, ontologically speaking, there is no ‘The Future’; there’s only futurity. Which is the point at which people say “oh, like the futures cone?” To which the reply is, well, which version? There are about twenty versions of that thing! And I think that all of them come from a place of good intention.

There’s also a truism—certainly in science fiction criticism, but also I think in the way that most engaged fans of the literature would talk about it—that science fiction isn’t about the time in which it’s set, it’s about the time in which it’s written. Whether that’s intentional or not... I don’t think it was intentional in the early days. Asimov in particular, I think he genuinely thought he was writing about the future, but looking back, it’s so incredibly obvious to us that, nope, he was writing about the futurity of the 1950s—which was a very, very different thing. But I think it’s also possible... we probably had to go through a period of believing in ‘The Future’ to get to a point where we can be sceptical of it; like, “OK, we tried that, we tried the monolithic and very technological-utopian ‘The Future’.” We can look back on writers like Asimov and we can see the yearning and the good intentions there, but we can also see the massive constraints of the ontology and epistemology of that time.

As for what you said about incompletion, I also talk about open worlds and closed worlds. One of the great cliches of writing advice that you get when you’re starting out... you’ve surely heard people say “show, don’t tell”, right? Now, like any rule of thumb, it’s actually highly contextual. But for me, “show don’t tell” ties to that incompletion idea you’re talking about: making people work for it a little bit. Don’t just give it all away, but put all the pieces out so they can put it together for themselves.

Because reaching that point of revelation independently... I imagine being a designer is a bit like being a writer, in that you start wanting to be a writer because you are incredibly moved by writing. And a lot of that comes from that sense of having those revelatory and visionary moments with books, and thinking “my god, one day I want to do that to other people!” And as you learn your craft and you read more and you become older—and some might say slightly more cynical as well—you realise there is an artifice to this, right? It is a craft; there are ways of pushing those buttons.

But: with great power comes great responsibility, right? You can use those buttons to various ends…

CT: One thing I might add in relation to “show, don’t tell” is a bit obscure; it comes from Elaine Scarry’s work, and I love everything she’s ever done. I would characterize her as a philosopher of literature, but she’s an English literature professor, and she wrote the most amazing book ever written called The Body in Pain. But Scarry also wrote this other book called Dreaming by the Book, and it’s mostly about Proust. All her stuff is very idiosyncratic, and Scarry does this extended analysis of how you feel the solidity of the imagined world in Proust—because it’s not just like a dream, in which everything’s gossamer. Scarry argues there’s a solidity to the ground and the walls Proust describes... it’s a big claim she’s making, but a lot of people think there is something about it.

In her analysis, Scarry says that whenever Proust is describing something physical, he never talks about it in isolation; he will always talk about something ephemeral moving in front of it. So it will either be the dappled light coming through the tree leaves onto sofa, or the curtain blowing in front of the wall. And she has this really idiosyncratic argument that, because of this movement over the surface of something solid, you background-feel the solidity of the wall or the sofa or the ground or whatever it is; the writing gives the sense of substance in contrast to what is moving. But Proust never tells you the wall is solid; he’s not even showing you the walls are solid! He’s showing you the curtain moving in front of the wall.

I think when you’re being really careful about being a designer or future worldbuilder, the things that you point to are not the things that you want to draw attention to. Again, it’s a kind of McGuffin strategy: I describe, or make, this thing, but in the end it’s actually not important; it is in the foreground, but what is important is the mid-ground context.

I’m thinking of one of Superflux’s scenarios in “Our Friends Electric” where people are in a kitchen, looking at a device that does the speaking for you when having a fight with an energy company. You know, the device is in the foreground—and the background is that people are still living in shared houses and renting, it’s still neo-liberal Britain basically. What is important is the mid-ground drama, the way the device is empowering those people. That’s the social practice that is being afforded, that is being offered for us to feel our way into, and take a stand on.

So I’m saying that sometimes when you say to designers “show don’t, tell”, they just go straight to showing the thing. It takes so long to teach them to not merely show one object or device, because it has to be two or three things in tension. But also, stage it: like, “you think it’s this, but it’s that!” That’s how you feel the prefigured probability of some vision.

PGR: By way of analogy, it’s like parallax tricks in video games, right? How can you conjure up that illusion of a depth of field... how can you do that, but in more than the visual sense?

CT: Yeah, that’s a great analogy.

PGR: I also think you’re talking about what Dan Hill famously called the dark matter, right? All the invisible stuff we just don’t talk about because it’s just there. How does that manifest? It’s invisible, but it’s matter: it has mass. It pulls things towards it. How do you surface that?

I want to return to the poverty of imagination thing you mentioned. You went to Graeber and Wengrove as your first example, and I was like “OK, we’re good!” Because I mostly associate that term, the poverty of imagination, very much with the Futures Literacy people—who I consider to be very, very well intentioned, but also very, very wrong. I’ve argued before that there is no poverty of imagination, and do that trick that Marx was fond of, the chiasmus: the problem is not the poverty of imagination, it’s the imagination of poverty! Yes, there are people who don’t have the capacity to imagine things as they might be in ten years’ time; that’s because they’re really busy trying to imagine how they’re going to get to the end of the month. People talking about the poverty of imagination who don’t understand poverty, unqualified... it’s not just a metaphor for most people.

CT: Exactly that.

PGR: The idea that we just need to teach people to imagine... so I ask people, tell me which of these two beings has greater imaginative capacity: a 35-year-old McKinsey consultant, or a 7-year-old who has just been told about dinosaurs? The point being, the capacity to imagine the absolute craziest shit is so innate in human beings, but it is trained out of us, methodically, ruthlessly. So rather than saying we can train people to imagine this or that, we have to instead stop training them not to.

CT: Can I just reformulate that a bit? So this is going to be a long shot, but: one of the problems is not imagining the future, it’s imagining people changing. It’s very difficult, and we don’t even notice it in ourselves, so it’s very difficult to even get people to remember.

I often do a thing where I’ll say to people, what’s something you used to like that you don’t like any more? Is there anything that you’ve gone off of? It could be a band, or it could be a vegetable, or it could be a person. How do you remember liking them? Can you possibly imagine remembering that you did like it, can you put yourself back there when you do any of these narratological tricks of incompletion and artefact? It’s almost impossible, of course.

What we’re asking people to do in terms of sustainability is to imagine being different people with different desires. You’re trying to say to somebody “imagine different pleasures”, which means “imagine being a different person”. Or, to put it another way—a really pedestrian way, which isn’t at all kind of poverty of imagination stuff—it’s the whole point of the “meanings” bit in social practice theory. The way I always describe it is to say to students, OK, there’s breakfasting, which has its breakfast things, and its skills, like a way to eat cereal so that the cereal doesn’t get soggy in the milk. But then there are the meanings, the pleasures: what makes a good breakfast? What is the ‘affective quality’ as Schatzki describes it, at the end of the process that makes you think you did it right? Because that’s the thing that’s regulating your behavior all through: like, this was a good breakfast, or I did good wandering, or this was a good commute. So convincing people about sustainable ways of living is about imagining different practice meanings, different affective qualities for your everyday practices, which is insanely difficult if not impossible. That’s not a child’s crazy imagination—but it will help, much more than the McKinsey, that’s for sure!

But that’s what we actually need to try and do. And because you can’t go straight to it, that’s exactly why we have to prefigure. You basically have to say, okay, let’s eat vegan for three weeks and then let’s really think about the pleasures that you’ve started to discover in this new thing, and not focus on all the loss. Let’s start thinking about what that is, and then let’s start imagining what it means to cycle after having had a vegan pizza, what it means to go dancing afterwards. Like, how do you begin to build out the world of that pleasure? Then you can start to actually imagine the pleasure—you’ve got all those other curtains in front of the meaning of the affect.

I think that’s the trick that I see in great novels that I don’t see in any design fiction: a recognition that it’s not the world that changes and we’re still the same. No—let’s imagine we’re completely different people with completely different pleasures. I think that’s a real skill to develop. How do you begin helping people see that they could live in a different way, could be different with different pleasures, different satisfiers, different drivers?

PGR: Yeah, that’s a really interesting way of putting it—but it underscores the extent of the challenge. The first comparison you went to there, I’ve seen this done in novels, but I haven’t seen it done in futures—maybe because with a novel, you’ve got 500 pages of someone’s attention. I work with narrative forms from my own futures, because that’s where I come from, and I think the place where that approach and design interact… as you were saying earlier, if you combine objects with textual framing devices, or literally combine the two. Documents from futures are a useful device.

But it’s like, OK, science fiction has developed an incredible toolkit for depicting futurity... I think of people like Cory Doctorow in particular, who’s got a real knack for presenting people who are recognisably human, but also clearly value really different things in really different ways to what we do. And I mention Cory as an example because he’s A) fairly well known, but also B) I think at the more accessible end of that. At the harder end, Greg Egan, for example, does it very well as well—and in certain literary senses he’s maybe the better writer, but he does not get the wide readership that Cory Doctorow has. Doctorow has that knack of approaching technology that way, and therefore surfacing some of the problematics of design in a way that people who don’t have any design literacy can nonetheless get to. The whole promise of cli-fi, of writing more novels about a climate-changed future, even if they are utopian—the people who are going to read those are already on our side! Maybe it would be nice if we could take everyone to the re-education camps and say, right, read some Richard Powers, read this, read that... but that particular medium lacks the immediacy required.

So you get to an interesting question here. Like, can you achieve this effect with cinema? Can you do it with TV and so on and so forth? I think it’s probably possible—but this is where you start having to bring in your kind of McLuhan-descended media theory: I guess you can, but these media are always their message as well.

We’ve managed to avoid talking about it so far, but I’m going to mention those two cursed letters: looking at so-called ‘AI’ from that perspective, as a medium that is so much its own message and literally nothing else... it’s just devoid of anything else at all. So it’s like, yes, you could—it’s not that you couldn’t, it’s just that it’s not going to happen. The sort of people who would go into that medium for any reason... even if you could spend the time to make the medium do that thing, the sort of people who are going to come to that medium aren’t going to want to encounter that sort of argument anyway.

CT: I think I want to do another stupid curtain/wall thing, here, which is to say yes, you need lots of words to do that worldbuilding, but the other issue is that often sci-fi is wrong because it’s about climate, whereas, you know, a decarbonised future is about eating pizza. Like, stop talking about the climate! There’s no fiction power to that.

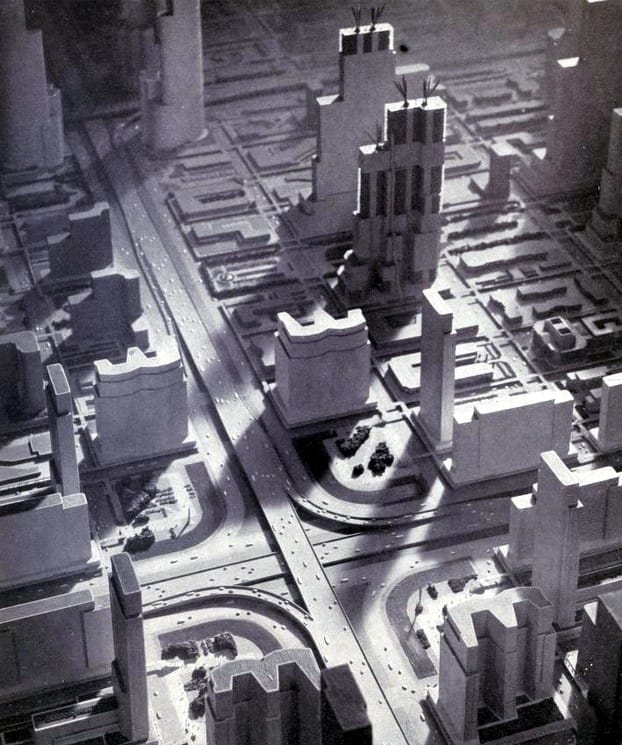

The fiction power, to some extent that’s the technique of spending a lot of time finding other pleasures that aren’t at all dependent upon oil-based systems; they can be in the present, distributed unevenly, or they could be in the past. I always have this argument with Gideon Kossoff, who I’ve worked with extensively on the transition design stuff with Terry Irwin at Carnegie Mellon University. He often uses examples of peasant village life from a century ago to show synergic satisfiers in Manfred Max-Neef’s sense. There’s a black-and-white old image that he used to teach with that depicts a group of women sitting around a common washing area doing the washing. They are clearly getting social needs satisfied along with cleanliness. Unfortunately, of course, the image speaks to an extraordinarily patriarchal and claustrophobic version of Gemeinschaft, everything that modernity supposedly liberated Europeans from.

I’m always like, how am I going to show that picture? It’s not a good idea to show that as an example of what transition design is about. But Gideon had this great counter-argument to me one time, saying yes, it was oppressive and there are things that could be criticized about it, but that doesn’t mean that its set-up is wholly part of that problem. It is classic modernism to dismiss all aspects of the past instead of retrieving good ideas, where possible, from those contexts. There would have been pleasures to living like that—and not only the pleasures of whoever was being oppressive, even the oppressed found pleasures in that vision.

These are examples of pleasures we’ve changed away from, but could recover. I spent a lot of time on Delores Hayden’s book on late 19th century material feminists, The Grand Domestic Revolution, this moment in which there was a convergence of socialism, feminism, and urbanization. And a bunch of women started doing architecture and designing intentional communities that was showing a completely different way of being in a city; they built the world sketched in a futurist story, like Bellamy’s Looking Forward, saying, this is what 20th century should look like. They were showing how to design into the city new versions of the pleasures in communal life.

You were giving examples before—my favorite is “The Matter of Seggri” by Ursula Le Guin, which is the account of men sort of living an upside-down version of a chivalrous life, fighting in order to then get the capacity to go into the fuckery and reproduce, while the women are the ones who actually control society. And it’s such a clever story because she creates a reversed feminist patriarchy but explains how most of these oppressed men really love that way of living: like, we don’t have to do anything, the food is cooked for us, and we’re just show-ponies, and our job is just to... yeah.

This is my answer to you: it’s insanely difficult, and maybe fiction is the only thing you can do it in, maybe it can be multimodal. But we do have lots of examples of alternative pleasures—and it could be, obviously not “The Matter of Seggri”, but something like that is going to be more important for thinking about a decarbonized future than the cli-fi stuff. And that’s the job right now.

My last example... sorry this is very obscure! Alan Stoekl is an American scholar of Georges Bataille, the proto-sociologist that wanted to form a cult in which people finally got to do human sacrifice. Bataille is the philosopher of excess. Alan Stoekl is a translator of that guy, but Stoekl is also a cyclist and translated a book about the philosophy of cycling, Paul Fournel’s Need for the Bike. As a result, in his other writings about sustainability, Stoekl describes in detail the pleasures of cycling, like the burning in your legs, but also—you know, it’s kind of almost early 20th Century futurist—the splatter of the street and weaving through traffic. It’s not at all the Copenhagen version of cycling, it’s the New York version of cycling. And Stoekl captures this very visceral Bataillean pleasure: people cycle, not because it’s more efficient or more green, but because they love the burning in their legs as they challenge cars up the street!

It’s a stupid example, in a way, because it’s preserving a whole bunch of nasty things that I’m not sure we want in our sociality. But it’s an example of visioning sustainable futures: the pleasure of burning thighs on a bike is the way of doing the transition to the decarbonized future. To do it more directly isn’t going to get us there; we need to be prefiguring being different people, and someone can do the analysis as to whether it’s going to be less carbon intense, and if it is, then we go with it. But you don’t try to design it from the less-carbon-intense position! You try to design it from new pleasures, recovered old pleasures, imagining crazy pleasures.

PGR: I think that’s a brilliant way of putting it. I think my argument is very similar. When I talk about world building, people assume I’m doing the thing that M. John Harrison famously railed against, right? You know, the clomping foot of nerdism: I sit down and I draw the map, and the people who live here are short, but they delve for gold! Now, with any fiction, there is obviously a builtness there—but going back to your point, it’s incomplete, even for me as its builder.

There are two schools of worldbuilding. I think some people are much more into that methodological end of it, but as I think Lincoln Michel said a little while ago, the people who really like that end of it very rarely actually get a novel written, because it’s kind of antithetical to story, right? You need to think about it, sure, but if you get too into designing how the language works... thinking about story is different to that.

I think one emerges from the other. I mean, story for me tends to always start from situations. I tend to think “okay, what if a world where this is like this?”—but I’m not detailing the whole thing, I just need enough room to put the characters in. Whereas some people are like “okay, I’ve got two characters, what room should I put them in?”

CT: But yeah, you don’t ever completely do either of them.

PGR: That’s right. I think the similarity we’re getting to... I mean, you said earlier that writing a novel that is specifically about the climate as it might become would be self-defeating, and not only because the audience that’s going to read it at all is probably already on side anyway, while the audience that you would rather reach, if it says climate fiction on the front, they’re going to be like “get the fuck out of here.”

But if there is a future in which we have really come to terms with the fact that the climate is changing, and accepted that it is down to us—in any such future, no one is going to sit around talking about climate change at all! That’s the definitional point: it won’t be ‘climate change’, it will just be how things are. It will be the dark matter. So again, you know, the toolkit of devices that science fiction has developed over the years to show-not-tell that dark matter—how do you get that dark matter in there, make it visible but without theatrically saying “oooh, look at the dark matter in the corner of the room”?

CT: The other thing that writers always say is that you have to start telling the story, and that’s how you realize what the fictional world is. You don’t start with the world, the story; you start with the characters, and then the characters tell you what they like to do and then you can start to construct the world around them.

This is the bit that people often forget about designers: they spend a lot of time not just designing a thing, but making a prototype of it and holding it in their hand and considering how someone might interact with it. It’s not human-centred design, but more like an artist finding the right kind of human: like “oh, this is for those types of people! I thought I was designing for these people, but this is for those types of people.” It’s important in the mix of everything that we’ve been saying to say this is the process component of world-building, the generative research version of world-building: learning by making a world, as opposed to thinking that the point is the final product of the world-building.

Comments ()